What has historical pregnancy testing got to do with arctic exploration and the expedition to rescue John Franklin, lost during his attempt to find a Northwest Passage? The idea of finding a Northwest passage, between the Pacific and the Atlantic oceans, was a long-held fixation; as early as the sixteenth century explorers had dreamed of it. Attempting to make that idea a mapped reality was perilous; those who attempted it were working at the extreme limits of endurance and at the edge of the known charted world. In contrast to the exotic problem that that search held out, the problem of pregnancy diagnosis was much more familiar, every day and domestic. Yet it was equally elusive.

These two exploratory fields are brought together in the extraordinary biography of Elisha Kent Kane, an adventurer, naval officer and doctor who was enlisted to go on Grinnell’s expeditions to find John Franklin in 1850 and 1853, the second of which he led. He graduated from the medical faculty of the University of Pennsylvania in 1842. The dissertation that he submitted as part of his training concerned experiments he conducted on the urine of pregnant and lactating women. His account of these experiments is full of odd case studies of women in the Philadelphia hospital, which give us an extraordinary glimpse of unpregnancy in the past.

In my Conceiving Histories project I am interested in the difficulty of diagnosing pregnancy and the time of not knowing – the am-I-aren’t-I time (that’s what I refer to as ‘unpregnancy’). I think that looking at the past before modern diagnostic technologies were available can give us ways of thinking about the times when our testing technologies aren’t useful, in the so-called two week wait before a pregnancy test, say, or in the weeks waiting for a viability scan. How did people try to know the body before our dipsticks and scans? At the very least I think that their endeavours testify to the fact that unpregnancy is a thing, that a state of indeterminacy is reasonably common, and that our abiding sense of a clear binary between not being pregnant and being pregnant is not exactly or not always how the (un)reproductive body is experienced.

One persistent idea, available throughout ancient, medieval and more modern medical writing, was that it might be possible to diagnose pregnancy by looking at and analysing urine in different ways. Of course urine testing has turned out to work like that, as it was always imagined it would. Technologies have to be imagined before they can be realised and so it has proved in this case.

Kane was impressed by work that had been done by a French scientist Jacques Louis Nauche in 1831. Nauche had identified a substance in the urine of pregnant women which he named Kiesteine. This is a word made from the Greek word for conception, κύησις [kyesis], made to look technical by adding -ine, an inflection which was being used to name elements and other substances in a new chemical vocabulary (think of words like chlorine and bromine and so on). Kiesteine was a precipitate which appeared in pregnant urine which had been allowed to stand. It formed a pellicle, a skin or scum, on the surface of the urine. That sounds pretty disgusting but the way Kane describes it makes it sound rather beautiful:

…a continuous scum of an opaline white or creamy appearance, with a slight tinge of yellow, which gradually becomes deeper and more decided. The uniformity of this colour, however, is generally broken by granulated spots of a clearer white, giving it a dotted or roughened aspect. The crystals of the forming stage now appear like shining points, and I have sometimes found numerous small brownish specks, sprinkled over the surface, not unlike the gratings of nutmeg.

Kane did experiments on the urine not only of pregnant women but also lactating women in the hospital and also checked his findings by doing studies of other test groups: people with pathological conditions of different kinds. He found that kiesteine could be found in the urine of pregnant women and that in lactating women it could sometimes be found, especially during weaning or when breast feeding stopped for another reason. Kane recognised his work to be operating in a long tradition extending back into the medieval and classical past. He appreciated that something very like Kiesteine had been described by medical writers like for example Avicenna, writing in the early eleventh century, and carried into Western medical literature. Kane noted that writing on urine often described pregnant urine as containing clouds, like carded wool, soft and webby. Carding wool is not something many of us do now, but it would have been a very familiar description to people before the industrial revolution.

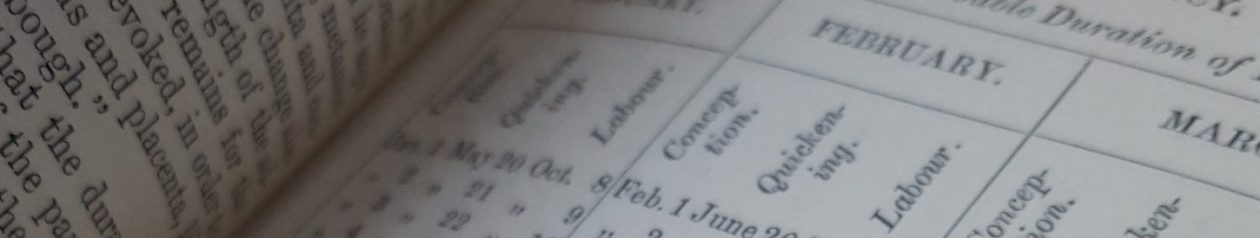

The case studies are perhaps the strangest part of Kane’s thesis and give us an oblique view of women caught in the in-between of unpregnancy. Kane reproduces some of his data in tables (above) and some as narrative histories. Those narratives are all about how he used kiesteine correctly to diagnose pregnancy in hard cases. We are sometimes given the names and ages of these women, and sometimes not; we are often told in which ward they were being treated. In some cases we know that these women are black or white, because they are patients in segregated wards. Some of them have had many children and are already mothers. The list includes women who are deliberately pretending to be or not to be pregnant, and others who are mistaken about their own conditions; in some cases Kane is just sorting those that are from those that aren’t, with little comment about what the women themselves thought, believed or tried to pretend. His testing technique is clearly particularly useful for achieving negative results which are often more elusive. After all, the birth of a baby is the surest sign of pregnancy.

I find these case studies hard to read. The details of these women’s lives rip vividly across time, but of course we have no way of finding out about how they felt either about being pregnant or not or winding up as a test subject in Kane’s experiments. The first on Kane’s list, Helen Anderson, may be a sex worker; she is being treated on the hospital’s venereal ward for gonorrhea and Kane describes her sexual habits pejoratively as ‘promiscuous’. Kane successfully diagnoses her pregnancy and she gives birth to a baby prematurely. Isabella Smith is 25 and comes into Kane’s data set from the white obstetrical wards. She seems to have a well-advanced pregnancy but it hasn’t been possible to do an internal examination because she has ‘epileptic paroxyms’ which result in ‘her temporary removal to the women’s lunatic asylum’, where Kane acquires a urine sample. Kane records her test as a negative which satisfy him ‘that she was an imposter’. Then, ‘during a well simulated paroxysm of epilepsy, her dress gave way, and disclosed an abundant mass of hair padding ingeniously arranged over the abdomen’. There is no hint as to her motive, why she might need to pretend. Another test subject, Maria Hero, is just 15 and borrows urine samples from her neighbour who isn’t pregnant, to hide her condition from the doctors.

Little disguises the note of triumph that Kane sounds at being able to see through women’s deceptions or, in cases where there is no attempt to deceive but a genuine confusion, to read through misleading symptoms. Clearly he understands his success to be measured in the admiration of his male colleagues who are sending him samples and marvelling that he can invariably make a correct diagnosis. Of seven samples they ‘presented under fictitious names, and at a distance of two miles from the place where they were voided’, Kane could perform the trick of correctly picking out the four cases of pregnancy. He shows no empathy for the women he researches, or any concern about the emergencies which may have brought them into his case notes.

Of the nine narratives that Kane details, three are pregnant and clearly resistant to being so, like Maria Hero. The others are not. One is the ‘imposter’ with the hair padding I mentioned above, but there are an astonishing four cases (of just nine) who clearly believe themselves to be pregnant, in whom ‘the evidences of pregnancy were well marked’, but who aren’t. The longest of Kane’s case note entries concerns 37-year-old Mary Welsh. Not only do her periods stop – they are irregular anyway– her abdomen is swollen, milk has come into her breasts, and she feels foetal movements. She is multiply examined internally and externally; doctors including Kane have listened with a foetal stethoscope for a uterine ‘souffle’ or foetal ‘pulsation’. These different physical examinations prove inconclusive. Kane’s observations of her urine convince him that she is not pregnant despite all this ambiguity; ‘much against her own wishes and those of her fellow patients’ he discharges her to the female working wards. She is undelivered of this phantom pregnancy at the time Kane writes, perhaps as much as year after she began to suffer.

Many years later, when Kane kits himself out for his arctic adventure, he clearly still sees himself as an experimental scientist, and his task as not only about finding Franklin. As well as making himself a wolf-skin robe, which he says ‘wandered down’ to him from the ‘snowdrifts of Utah’, and getting some good warm knitwear, he buys himself ‘instruments for thermal and magnetic registration’. His journey notes are full of his findings and thoughts on all sorts of natural forms and phenomena, as well as the indigenous people that his party meets on its way. On his trip, he turns his considerable powers of observation and description from the specimen bottle to these exotic novelties. Kane notes, though, that there is much that surpasses his ability with words, so that he confesses himself

…amused with the embarrassments which my journal exhibits in the effort to describe [the icebergs]. Certain it is that no objects ever impressed me more. There is something about them so slumberous and so pure, so massive yet so evanescent, so majestic in their cheerless beauty without, after all, any of the salient points which give character to description, that they almost seemed to me the material for a dream, rather than things to be definitely painted in words.

Kane’s expedition never did find Franklin, just the remains of his winter camp. Experiments into kiesteine went nowhere. Here, then, are two dead ends in the map of history. Both eluded the efforts of Kane and others to define and settle them. Whatever clarity kiesteine gives Kane, it is firmly dismissed as nonsense by the scientists in the early twentieth century, who developed accurate animal tests. Neither his work, nor that of others who were also experimenting with kiesteine, fed into modern diagnostic practice. Experiments into kiesteine were overtaken by other means and ways of discovering pregnancy.

Kane’s account of the unpregnant women in Philadelphia Hospital show us of course that men had a curiosity and investment in clarifying and settling pregnancy diagnoses, but there are also hints here about how it also must have mattered to women, many of whom were suffering with symptoms but never delivering. For scientists like Kane, unpregnancy was an exciting exploration into uncharted and unknown places, full of puzzles and wonders, but for the women on whom he experiments, unpregnancy was a very cold and hostile wilderness in which some were hopelessly lost and from which there was little or no hope of rescue.

References:

Elisha Kent Kane, ‘Experiments on Kiesteine’, American Journal of the Medical Sciences 4 (1842): 13-38.

Elisha Kent Kane, The United States Grinnell Expedition in Search of Sir John Franklin: A Personal Narrative (Philadelphia: Childs & Peterson, 1856).

Featured Image:

Ship model, thought to be of HMS Erebus, one of the ships that John Franklin led in his 1845 expedition. © National Maritime Museum Collections