As soon as the doctor told her she was pregnant, she felt frail and nauseous, although she had not done so before.

‘But are you sure?’ she asked, foolishly, she felt, picking up her skirt and stockings. The doctor was washing his hands.

‘Oh yes,’ he said. ‘No doubt. Better book you into a maternity hospital.’

She laid a hand wonderingly on her stomach.[1]

This is how the writer Angela Carter imagined a pregnancy diagnosis at eight weeks in her unpublished short story ‘The Baby’ from about 1961. The skirt and stockings on the floor, the doctor washing his hands: Carter imagines an internal examination. ‘The Baby’ is intended to be naturalistic – a woman discovers she is pregnant and worries, particularly about her relationship with her partner. The story is mostly not magical realism of the kind that made Carter famous. However, an eight week pregnancy couldn’t, indeed still can’t be, determined by internal examination and so the story in this excerpt is inadvertently magical, more like a fairytale than anything true to life. Carter imagines the doctor here as all-knowing, even as having special powers.

One of the things that the conceiving Histories project is trying to do is to look at the history of not-knowing, a history of the time when people are wondering ‘am I? aren’t I?’. Part of what we want to look at is the search for a diagnosis in that in-between time and the desires and fantasies generated in ignorance. In ‘The Baby’ the protagonist feels foolish because she doesn’t know and the doctor does. But there is an even more profound unknowing which may be the source of the sense of foolishness described here.

Before it was possible to piss on a stick to determine pregnancy, urine was injected sub-dermally into animals. For much of the twentieth century it was frogs, mostly South African clawed xenopus laevis toads – aquatic, carnivorous and tropical. Frogs because they emitted eggs externally and did so in reaction to the injection of pregnant urine, and so didn’t have to be dissected to get the result. As Edward Elkan, a doctor who kept a hundred frogs in a tank on the balcony of his flat overlooking Regents Park for testing his private patients in the 1930s, wrote: the xenopus test has the advantage over other tests which require ‘hecatombs of young mice’.[2] The test was as accurate as our pregnancy tests are today.

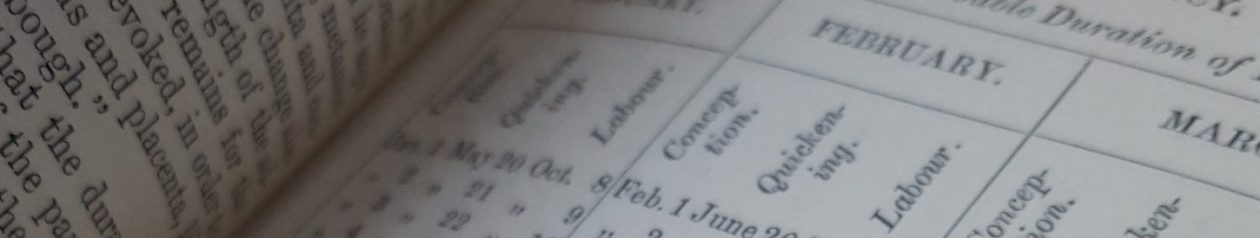

The logistics of this test, as it developed in the ‘40s and ‘50s are extraordinary. Women’s urine was sent with a fee by post from doctors’ surgeries and pharmacies to diagnostic centres where it was injected into frogs which had been sent by ship from South Africa. The Family Planning Association archive, at the Wellcome Library, is full of documents about the international transport in these frogs.[3] The FPA got their frogs from Peers Snake Farm and Zoo in Cape Town, through an animal transport agent, Thomas Cook and Sons.

They bought them in batches of 500; mainly these were female frogs but sometimes also male ones. They started getting them in 1949 and stopped in 1963 when immunoassay tests were available. The frog supply was dependent on the weather and the health of the population; sometimes they died in transit. One of the main questions which dogs the archive, to give a sense of the logistical challenge presented by this test, is whether it is cheaper to ship back the containers that the frogs came in or buy new ones each time.

Pregnancy really wasn’t diagnosed through internal examination, then, in the way that Carter imagines in ‘The Baby’. This lack of knowledge isn’t peculiar to Angela Carter. Most people didn’t know how pregnancy was diagnosed at the beginning of the 1960s; lots of medical practitioners themselves had no idea. Lots of people don’t know today that this was the way that pregnancy testing was done for most of the twentieth century.[4] Women got their results from doctors, rather from the test centre itself. Because tests were usually done in extremis, the result was no doubt the important thing, rather than finding out how the trick was done.

The Family Planning Archive is full of all sorts of documents about this test but what isn’t in the archive is much about women themselves, the people being tested. So, on the one hand, we have Angela Carter’s story and a lack of knowledge about how a result was achieved, that is how pregnancy was diagnosed and, on the other hand, the archive articulates an equivalent ignorance or at least a lack of curiosity about the people whose urine was being tested in the frog labs. The labs tested urine, not people.

In response to this, Anna Burel, who is making artwork as part of the Conceiving Histories project, has set about the task of creating a fictional archive which re-introduces the idea of the tested woman missing from the archive.

She is using the forms of the documents in the Family Planning Archive to do this, picking out the visual elements of telegrams which went backwards and forwards between the Association’s diagnostic centre in Chelsea, Thomas Cook and the snake farm in Cape Town.

She has also made a number of plaster frogs, each has its own type written label, marked with the name of a fictional person. Each of those tags corresponds to the label on a urine sample bottle.

Making fictitious matches between frog and urine, by inserting names, Anna’s work is trying to close the gap between the diagnostic centre, and what went on there, and the lives of people who sent in their samples and waited for results. She is presenting, through the gesture of her figures, an impression of their responses to their results.

Anna and I have been thinking a lot about the annunciation, in relation to the whole project, as a pregnancy test before such things existed; no doubt there’ll be another blog post about it. What a wish-fulfilment fantasy: someone will come from another world and tell me the answer. We have been thinking about the annunciation, too, in relation to the lack of knowledge of the urine/xenopus test. In the traditional idea of the annunciation – when the angel Gabriel tells Mary that she’s going to have a baby in the Gospel – Mary’s pregnancy isn’t just announced it is also brought into being at exactly the same time. Often this is depicted in medieval art by a ray of sunlight, coming through a window, beaming onto or into Mary, sometimes carrying a little image of Christ or the holy spirit in the form of a dove.

Returning to Angela Carter’s imagined scene, she describes something rather similar. The doctor knows by putting his hands inside her, penetrating her in a mundane version of the divine conception. He magically reports and also symbolically impregnates, putting the foetus into the womb by hand.

Given the lack of knowledge about diagnostic practice, women might as well have been told their results by angels, the diagnostic centre was as remote as the other, spiritual world from which angels are thought to come.

[1] ‘The Baby’ (c. 1961), London, British Library MS Additional 88899/1/42

[2] Edward Elkan, Sketches from my Life, (1983), p. 56. London, Wellcome Library MS 9151.

[3] London, Wellcome Library, SA/FPA/A3/11/13: Box 23.

[4] One person who does know is Cambridge researcher Jesse Olszynko-Gryn. He is currently preparing a book on the history of pregnancy testing. You can read some of his work and find out more about the xenopus test here.