Last year Anna and I queued along The Cut at the Young Vic Theatre for returns to see Yerma, an adaptation of the Federico García Lorca play by Simon Stone. There weren’t any. But this week I had the chance to see it at a nearly empty cinema in a soulless shopping centre off the M25 as part of the National Theatre Live programme. Weird, not quite the same, but we take what we can get sometimes.

The play, people may know, tells the story of an unnamed woman (played by Billie Piper) unable to have a child with her husband John (Brendan Cowell). The action takes place in a glass box which mostly represents the couple’s new and big empty house, although also sometimes other places. Watching the action as if in an aquarium, the audience comes to represent the social expectation that couples become parents and the pitying social response when they don’t. The central character writes a blog about her ‘journey’ full of confessional information: about her resentment for her pregnant sister, for example, and her partner’s lack of co-operation with ‘baby-making’. Similarly, in the play’s action, then, the world looks in through see-through walls.

One wordless scene is played out to soaring baroque music – Pergolesi perhaps. The box is suddenly furnished with sofa, a kitchen island, a child’s cup on the floor. John and his partner are bouncing a baby boy in a sleep suit. Later, it turns out, the child is not theirs. When they return him to his mother the box is empty once again. I was as drawn to this play as others have been. The energy and commitment in the performances moved me, of course.

I wanted to see Yerma because the Conceiving Histories project is so embroiled with the questions it raises: about waiting and disappointment, about not being pregnant and not having a child. As I look through different historical literature for accounts of these experiences I am continually struck by the same story of the mad woman, made mad by her childlessness. This woman stands in the centre of our understandings of childlessness. Similar characters, albeit a great deal less convincing, turned up in the recent series of Top of the Lake, for example. Here, women who are unable to have children resort to exploitative surrogacy arrangements using immigrant sex workers. One particular woman is driven mad enough to dance in and out of the traffic wearing her nightgown. She’s the Gothic version, embroiled in the dark secrets in which Gothic fiction revels. Yerma, in contrast, is more statuesque and, because the whole play is given over to this figure, more like a Greek tragedy. In whichever version, this woman steps out from the past to confront our own modernity; Yerma’s heroine has twelve unsuccessful rounds of IVF.

Part of the need for this mad woman is to do with how stories work. The narrative about wanting to have children either finishes with the person having a child or it doesn’t. But how can the latter story really work dramatically? If they don’t have a child then something else has to happen: so, they go mad. Can’t we think up some other endings, I wonder as I leave the cinema. When I voice this to my partner who watched Yerma with me, he replies: ‘Well, what do you want? A play where at the end the main character says, “I am a bit disappointed, but I’m soldiering on”?’.

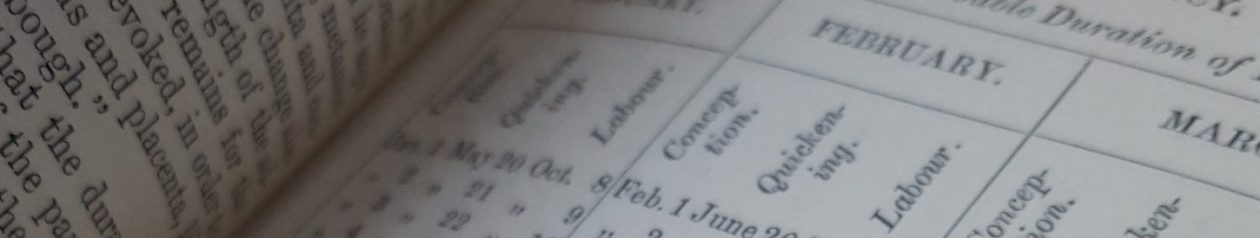

I’m working on the answer to that question and it involves thinking about this mad, childless female figure and our cultural investment in her, but it also involves finding out other endings for this story by looking at documents from the archives, imagining the powerful, dramatic ways in which we might tell the potentially boring story about ‘soldiering on’, of nothing happening, of stories that don’t end happily or don’t end at all.