This post has been contributed by Dr Luca Andriani (Birkbeck) and originally appeared on The Mint magazine.

Luca Andriani and Gaygysyz Ashyrov explain how life satisfaction is not a gold-plated toilet brush.

Laura Kovesi was chief prosecutor of the Romanian Anti-Corruption Directorate between 2006 and 2018. She convicted over 1,000 Romanian public officials for corruption and electoral fraud. Those officials included city mayors, government ministers and leaders of ruling parties. In 2018 Kovesi was fired by the Minister of Justice accused of undermining, with her actions and behaviour, the integrity of the Romanian institutions.

Kovesi’s story is one of a long list of tales of corruption and bribery that is endemic in East European countries and former members of the Soviet Union. The latest one being that of the leader of the Russian Opposition and founder of the anti-corruption foundation, the FBK, Alexei Navalny. The latest instalment of his ordeal began with his arrest on January 17 on returning to Russia after surviving an attempt to poison him. His detention was for his release of a detailed video showing a $1 billion palace that he alleged was built secretly by Russia’s president, Vladimir Putin, using bribes paid in exchange for political and business influence.

In response to the Kremlin’s actions, thousands of Russians started a protest march against the Kremlin leader. They held aloft gold-painted toilet brushes allegedly resembling those found in the palace.

Informal payments and clientelism are part of the inheritance from the central planning economy of the former Soviet bloc, where they were an essential feature to counteract the dysfunctional system. This inheritance not only affects the public realm but also the life of private individuals. Bribes and informal payments are often the route to access basic needs and services, including medical treatments and business licences.

Fighting these corrupt acts is possible. For a period, Kovesi provided an example of what is possible when formal institutions punish criminals even amongst the elite. However, formal institutions are not enough. Kovesi was eventually sacked, while the Russian protests show the importance of social movements when formal institutions are themselves corrupt.

Kovesi provides an example of what is possible when formal institutions punish criminals even amongst the elite.

So, what are the conditions that make civic rebellion against endemic corruption more likely? Could citizens’life satisfactionbe a factor in whether they accept corruption? We decided to test this in Eastern European and countries of the former Soviet Union.

Besides being afflicted by relatively diffuse corruption, the former Soviet-bloc countries are also new democracies. Researchers believe that the transition of these countries from communism to new democratic regimes has triggered a widespread feeling of uncertainty in their citizens. In past decades, for instance, Eastern European citizens had to adjust to new laws, a more competitive job market, different bureaucratic procedures, changes in education and so on. So, although these reforms have contributed to continuous economic improvements, happiness has increased at a lower rate due to the resulting stress.

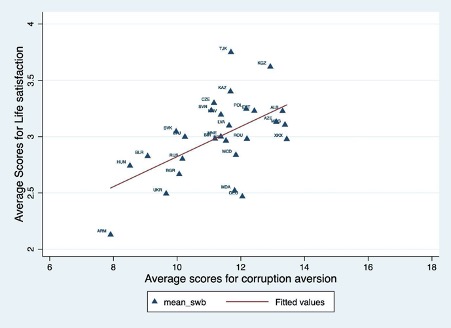

We compared citizens’ self-evaluation of their quality of life with their attitudes towards corruption. The results show that countries scoring higher in life satisfaction tend to score high also in corruption aversion (see figure 1). Respondents who are more satisfied with their life tend to be more willing to report cases of corruption. Happier citizens are stronger in their belief that ordinary people can make a difference in the fight against corruption than their unhappy co-citizens. Indeed, more deprived socio-economic conditions lower citizens’ conformity to formal rules. For instance, individuals with difficulties in accessing health care and education services due to low socio-economic status are more likely to become victims of corruption.

These results drive towards important reflections in terms of policy implications. Citizens’ happiness is not only a human prerogative, but also should be a priority for benevolent members of the ruling elite seeking to reduce the costs of corruption to society and the economy.

So, improving citizens’ life conditions could increase their loyalty towards the public authority and their compliance with legal rules and laws. Nevertheless, this should be a warning for advanced economies. Increasing inequality and a consequent decline of individuals’ life satisfaction, could drive citizens to become less compliant with rules, and more tolerant towards anti-social behaviours. Those at the bottom of society, who seek to play the system, are highly unlikely to be dobbed in by their peers. More likely their peers will seek to learn similar tricks.

We can say, then, that happiness has economic value because anti-social and illegal behaviours bring increasing monetary costs for the entire society. In this respect, reductions in happiness and life satisfaction can sound a warning that more costs are on the way in a negative feedback loop. While increasing in happiness does not necessary mean that corruption will end, it will make it less tolerated – a key condition for fighting corruption.

We can say, then, that happiness has economic value .

What about Eastern European and former Soviet Union countries? Democratisation clearly does not automatically translate into less corrupt governments and societies – many people in those countries don’t comply with the rule of law. This may persist as long as they have something to gain. However, should the costs of corrupt behaviour trigger a movement for change, state actors might then have to give up something to avoid social unrest and increase state loyalty. This continuous negotiation is a very long journey. Raising thousands of gold-painted toilet brushes into the air might be good as a start to fight corruption but clearly there is a long way to go.

Luca Andriani is a Lecturer of Economics at Birkbeck university of London, Co-Director of the Centre for Political Economy and Institutional Studies (Birkbeck), Director of the MSc Business Political Economy and Society and founder Director of the video series 5-Minute. His research interests are on individuals’ attitude towards corruption, trust and tax evasion and how these attitudes influence the governance of the state-citizens relationship.

Gaygysyz is a research fellow at School of Economics and Business Administration, University of Tartu, Estonia. His research area covers corruption studies, institutional economics, microeconomics.