Artist, campaigner and facilitator of creative projects Dr Lizzie Burns writes about the effects of boredom and how to counter them.

During this time of lockdown, ‘boredom’ has been acknowledged as a challenge. But whilst children readily express their frustration with being bored to their parents,1 boredom is rarely acknowledged by adults as something they can suffer from.

Whilst working as a Public Engagement Consultant within the Hidden Persuaders project, I have encountered new ways of thinking about boredom, including through reading about ‘sensory deprivation’. This state is caused by the deliberate reduction of stimuli from one or more senses. The idea that boredom might be damaging to mental health has a long history. The problem was taken up in various ways during the post-war period. For example, in 1957 Woodburn Heron published an article in Scientific American entitled ‘The Pathology of Boredom’.2 The article describes experiments on adults designed to investigate the effects of prolonged exposure to monotonous environments. Heron suggested that monotony was an important and enduring human problem. Boredom’s tendency to create disturbances in perception was a factor contributing to accidents, for example, as can be observed when pilots take long flights.

Wider efforts to re-explain and re-define extreme boredom as sensory deprivation can be dated to a symposium held at Harvard Medical School in 1958. These papers were published in 1961 as a book called ‘Sensory Deprivation’.3 This research was actively encouraged through funding from the Canadian Research Defence Board, who were interested in discovering ways to make the mind vulnerable to manipulation (‘brain-washing’).

In this book, Heron wrote about the grim practicality of studying boredom for researchers: ‘the subject himself did nothing for 24 hours a day, which is difficult’ while ‘the experimenter did nothing for 8 or sometimes 12 hours a day, which sounds easier, except that the subject was all through in four or five days’. But the work was short-lived; as difficult as it was for the subjects to dwell in boredom, it was even more challenging for the experimenters themselves, who had to observe them.

Whilst the ‘sensory deprivation’ experiments that took place during the 1950s feel not only disturbing, but unethical by today’s standards, at the time, much of the criticism levelled against them stemmed from the fact that students were allegedly being paid to do ‘nothing’. To minimise stimulation, students were instructed to wear a visor, gloves on their hands with cardboard cuffs, and listen to white noise. These conditions resulted in sensory deprivation experienced as disturbed cognition. Heron reported that students who had intended to use the time in isolation productively, found that their thought-patterns became disordered and were sometimes accompanied by hallucinations.

In animals, however, the need for stimulation and enrichment had already been recognised. Heron’s mentor, Donald O. Hebb, found in 1947 that rats that had been raised as pets, with regular interaction, performed better at problem-solving tests than those who were raised alone.4 In the 1960s, Mark Rosenzweig compared the brain development of rats left in isolation, in bare cages devoid of company and stimulation, with rats who were left with toys, ladders, tunnels and wheels5. He found that environmental enrichment directly affects brain development, with increased cerebral cortex thickness (3.3-7%) and around 25% more synapses.6-8

My interest in boredom comes from working in hospital as a Creative Specialist offering creative activities to adults in Oncology, as a way of supporting patient and staff wellbeing. In this work, I grew especially interested in the predicament felt by many patients suffering with cancer. They often describe a feeling of ‘chemo head’ and say they struggle to focus. I found that providing engaging and inspiring activities allows patients to focus for prolonged periods. This suggests that ‘chemo head’ results, in part, from the mental state of the patient rather than simply the physical effects of chemotherapy treatment.

One patient I visited had become creative on his own accord and started drawing colourful pictures of cars based on memories. Leonard was 68 and had not drawn since childhood. I asked why he started drawing as an adult and he explained it directly as ‘boredom’. Leonard said that his boredom resulted from being left alone in a bare room, without TV or books. After a week he asked a nurse for pens and paper and started drawing. Initially, he was unsure if his drawings were ‘any good’, but had an interested and enthusiastic response from the nurses. Their continued interest spurred him on, and eventually we organised his first art exhibition, which was displayed in the hospital.

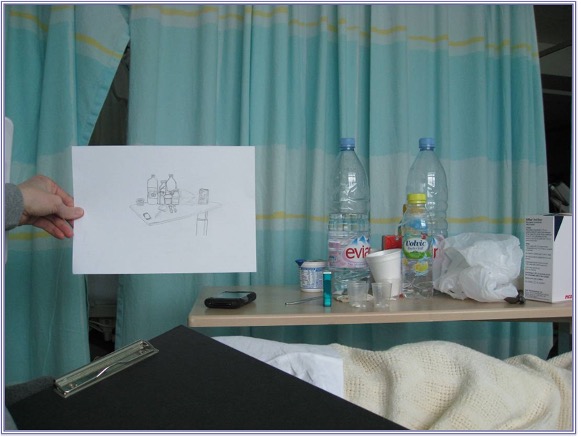

During one of my first experiences working in a hospital, I visited one young adult male patient who twice said ‘no’ to creative activities. After a third visit, he agreed because he explained he felt so bored that he ‘might as well try’. During the creative session, the patient sketched objects on his table and entitled the sketch, ‘boredom’. It was only years later in my work that I recalled this encounter as recognising boredom. And it was only through working with Leonard that I began to see boredom as a significant and under-recognised aspect of being an adult hospital patient.

In the 1960s, experiments on rats that exposed the importance of sensory stimulation for healthy brain development also pointed to the importance of enriched environments for children for their healthy development. The Platt Report (1959)9 explored the welfare provisions for children in hospitals and underscored the value of ‘play’ in helping children deal with emotional separation from their mothers.

Susan Harvey, a Save the Children Fund adviser, stated in 1972 that ‘deprived of play, the child is a prisoner, shut off from all that makes life real and meaningful’.10 Enriching hospitals wards through the provision of toys and play-specialists brings support to children and helps avoid the pitfalls of sensory deprivation. More flexible visiting hours allow for parents and other companions to visit more easily. But for adults, the need for enrichment has still not been fully recognised. Experiments with young rats showed a measurable difference in brain development due to the ability to adapt and change, called ‘plasticity’. For humans, the fact that plasticity continues throughout life suggests our need for continued interaction and stimulation.

Children’s wards today are colourfully decorated with opportunities for interaction and play. This is in contrast to adult wards which are often bare or decorated with images relating to illness, which may trigger anxious feelings and mind-wandering. There are no adult equivalents (beyond young adults) to ‘play specialists’ and few activities are offered for mental stimulation. The beeping of machines interferes with a patient’s ability to focus. Routines, bland food and restrictions of staying indoors are all additional factors which inadvertently encourage boredom. Many patients describe struggling to focus on reading, which is an activity that could ideally provide the mental stimulation so desperately needed. And a further complicating factor to boredom is an underlying anxiety – subtle or extreme – about the patient’s own health, and the reasons behind the hospital stay.

One patient I encountered suggested origami as a way to help inspire and calm other patients. Origami is a creative activity working within the constraint of folding, mostly from a square of paper. Paper was invented in China around 2,000 years ago. The origins of origami came from Buddhist monks bringing this new material to Japan where it began to be used in religious ceremonies. The practice has evolved and origami can be given as gifts at Shinto weddings and between Samurai warriors. One suggestion behind the philosophy of origami is the notion of ‘honouring the paper’. Paper folding also offers a sophisticated form of playful activity suitable for adults using an everyday cheap material to provide physical interaction and mental stimulation. Patterns are passed from one person to another, bringing a sense of human connection even when performed alone. Designs represent flowers, animals or other symbols which are rich in meaning. Origami requires considerable focus which can combat mind-wandering, and overcoming challenges can bring a sense of achievement.

A series of experiments by Wilson et al. described in the journal, Science, published in 2014, is reminiscent of Heron’s report in exploring the effects of monotony. In this 2014 study, students were asked to sit in an unadorned room for a brief 6-15 minutes and simply do nothing.11 Most participants tried to do something. In the following experiment, Wilson et al. provided an option for participants to self-administer a mild, but unpleasant electric shock. They found 67% of men and 25% of women shocked themselves, often repeatedly, rather than do nothing. The authors concluded that ‘people prefer doing to thinking’ and that ‘the untutored mind does not like to be alone with itself’.

For adults in hospitals, time spent alone in unadorned rooms can be considerable. My time spent observing this boredom led me to write an article about the topic for the British Medical Journal. I was also motivated to write this as a response to another paper, published a decade earlier, which disturbingly suggested the use of medication to combat boredom in Oncology. The idea of administering medication for boredom, especially when there are so many cheap interventions available (like a simple pen and paper) struck me as deeply concerning.

My article encouraged recognition of boredom as an under-acknowledged form of suffering for patients, and called for more imaginative, successful and humane options to help address boredom.12 After some patients described boredom as a kind of torture,13 I was spurred on to start the Anti-boredom Campaign.14 One of the things I offer is origami as a way of creating mental focus involving patterns. An interesting link between origami and sensory deprivation experiments is that boredom can be induced through lack of patterns. Origami is therefore an effective way of lifting mood and dispelling the unpleasant ‘pathology of boredom’.

Boredom is often trivialised by others, and I wonder whether this comes from our deep dislike of this state which is socially acceptable to talk about as a child, but less so for adults. Boredom has not been widely recognised in hospitals – not through a lack of compassion, but because, characteristically, patients do not openly speak of being ‘bored’, as is the case more widely in society.

The Anti-boredom Campaign emerges out of this work,12 and I have also found widespread support from healthcare workers (who are often under too much pressure to address this themselves). Funding and research is needed to recognise and address boredom in hospitals as part of the emphasis on compassion-based treatment. In the context of the pandemic, boredom is an even more challenging problem as patients often cannot have visitors.

But for us at home, what can we do to fend off the boredom we are all suffering from? When I am asked this question, as so often I am nowadays, I often begin with a note of encouragement. Simply looking closely at nature, and registering the constant changes can delight the senses. Wherever possible, we can also try to give ourselves variety in what we do/wear/eat/read, challenge ourselves to try new things and pursue meaningful social connections. These are all vital ingredients for maintaining wellbeing17. I have also sought to encourage others to take up origami and the opportunity for creativity it provides. Indeed, I hope that some of you reading this blog may consider my weekly live origami workshop to bring a new challenge into your life. From a piece of paper the possibilities are endless…

- Waldbieser J (Nov 3rd 2020) ‘Escape the Boredom Trap’ – The New York Times https://www.nytimes.com/2020/11/03/parenting/boredom-kids-pandemic.html

- Woodburn H (Jan 1957) ‘The Pathology of Boredom’ – Scientific American 196; 1

- Solomon P, Mendelson JH, Kubzansky PE, Trumbull R, Leiderman PH and Wexler D (Editors) ‘Sensory Deprivation; A Symposium Held at Harvard Medical School (1961), Harvard University Press

- Hebb DO (1947). “The effects of early experience on problem solving at maturity”. American Psychologist. 2(8): 306–7. doi:1037/h0063667.

- Krech D, Rosenzweig MR, Bennett EL (December 1960). “Effects of environmental complexity and training on brain chemistry”. J Comp Physiol Psychol. 53(6): 509–19. doi:1037/h0045402. PMID 13754181.

- Altman J, Das GD (December 1964). “Autoradiographic Examination of the Effects of Enriched Environment on the Rate of Glial Multiplication in the Adult Rat Brain”. Nature. 204 (4964): 1161–3. Bibcode:204.1161A. doi:10.1038/2041161a0. PMID14264369. S2CID 29794121.

- Diamond MC, Krech D, Rosenzweig MR (August 1964). “The Effects of an Enriched Environment on the Histology of the Rat Cerebral Cortex”. J. Comp. Neurol. 123: 111–20. doi:1002/cne.901230110. PMID 14199261. S2CID 30997263.

- Diamond MC, Law F, Rhodes H, et al. (September 1966). “Increases in cortical depth and glia numbers in rats subjected to enriched environment”. Comp. Neurol. 128 (1): 117–26. doi:10.1002/cne.901280110. PMID4165855. S2CID 32351844.

- Platt, Sir Harry; Ministry of Health (1959). “The Welfare of Children in Hospital”(PDF). Internet Archive. University of Southampton: HMSO. Archived from the original (pdf) on 1959. Retrieved 26 April 2018.

- Jun-Tai M (2008) ‘Play in Hospital’ https://www.thetcj.org/in-residence/play-in-hospital

- Wilson TD, Reinhard DA, Westgate EC, Gilbert DT, Ellerbeck N, Hahn C, Brown CL and Shaked A (2014) ‘Just Think: the Challenges of the Disengaged Mind’ Science 345, 75-77

- Burns EM (2017) Pass me an Anti-boredom Pill Doctor’ BMJ Opinion https://blogs.bmj.com/bmj/2017/03/02/elizabeth-burns-pass-me-an-anti-boredom-pill-doctor/; Smith J (2018) ‘The Malady of Boredom’ BMJ Opinion https://blogs.bmj.com/bmj/2018/11/29/jeremy-smith-the-malady-of-boredom/; Smith J (2018) ‘The Malady of Boredom’ BMJ Opinion https://blogs.bmj.com/bmj/2018/11/29/jeremy-smith-the-malady-of-boredom/

- Anti-boredom Campaign https://antiboredomcampaign.wordpress.com/

- Burns EM (2019) ‘Elephant in the Ward: Boredom in Hospitals’ BMJ Supportive & Palliative Care 9(2) http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmjspcare-2018-001615

- Acclaimed artists contribute to new ‘Boredom Buster’ newspaper (2020) – https://www.uhbw.nhs.uk/p/latest-news/acclaimed-artists-contribute-to-new-boredom-buster-newspaper-for-the-nhs

- Burns L (2020) ‘Transforming the everyday into something beautiful; How origami can encourage self-care’ https://blogs.bmj.com/bmj/2020/12/21/transforming-the-everyday-into-something-beautiful-how-origami-can-help-encourage-self-care/