A mapping of the UK university system

Since the 1980s European universities have adopted decision-making processes increasingly based on professional management and accountability, where numerous internal and external stakeholders play a progressively greater role in shaping universities’ activity profiles. Additionally, several countries including the UK have introduced market-type incentives that encourage universities to behave strategically and particularly to engage in activities where they enjoy some form of advantage over their competitors. This is expected to fuel institutional differentiation: universities with different resources and different know-how will focus on different activities and address different opportunities and needs in their socioeconomic contexts, satisfying the expectations of different stakeholders.

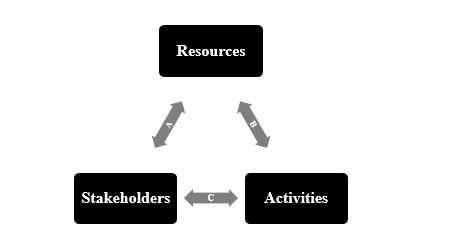

So far, very few studies have explored the extent to which universities’ resource and activity profiles – intended in a comprehensive way to include teaching, research and socio-economic engagement – align with their strategic prioritisation of different stakeholder groups. This study explores the complex associations between universities’ institutional resources, stakeholder prioritisation strategies, and activity profiles, in order to better understand the different ways in which universities drive socioeconomic development.

To address this issue, we originally combine Multidimensional Scaling (MDS) and multinomial logistic regression techniques applied to data on universities in the UK. Results indicate that UK universities have very varied resource and activity profiles. We distinguish four main profiles emerging from the MDS analysis: (i) ‘science-based highly research intensive’ universities (SHRI) (ii) ‘mixed profile research intensive’ universities (MPRI); (iii) ‘professional teaching intensive’ universities (PTI); and (iv) ‘arts and humanities-based teaching intensive’ universities (AHTI). These profiles appear to show consistent patterns:

- between institutional resources and activities performed: SHRI and MPRI profiles are more likely to apply to old universities specialised in medicine and science and engineering, PTI profiles are more likely to apply to former polytechnics or modern universities specialised in the social sciences, and AHTI profiles are more likely to apply to higher education colleges or modern universities specialised in the arts and humanities;

- between the teaching and research activities of universities and their socio-economic engagement profiles: SHRI and MPRI profiles focus on patenting and research contracts and PTI and AHTI profiles focus on courses for professional development and public engagement; and

- between stakeholder prioritisation strategies and resource and activity profiles: universities prioritising industry stakeholders are more likely to have a SHRI or MPRI profile and those prioritising employers are more likely to have a AHTI profile.

These results reflect a persistent division between old research-oriented universities and more recently created universities, particularly those that were formerly vocational education institutions. One of the causes may be strong mutual interdependence between universities’ institutional resources, activities and priority stakeholders. This creates strong path dependency in the system – universities’ historical configurations still affect their current ones – but also entails that a change in any of these elements may trigger transformations in the other dimensions. Universities’ strategic decisions should take into account such dynamics. For example, if a PTI university decided to prioritise their relationship with industry researchers outside the region, they might find this quite difficult to accomplish, because their resources and activities would lead them to privilege local stakeholders and particularly employers. However, if they succeeded, this would have implications for their resource and activity profiles, getting them closer to a SHRI or MPRI profile in the medium-long term.

Finally, this strong differentiation means that universities will not respond in the same way to the same incentives. Policies aimed at supporting engagement with certain types of stakeholders will only work if the institutional configuration is favourable to developing that kind of engagement. For example, SHRI universities that attract internationally mobile graduates would not be strongly receptive to policies aimed at helping universities to improve their graduates’ local employment prospects. Policymakers should bear in mind interconnected stakeholder-resource-activity profiles in order to design effective initiatives.

The findings of this study are reported in: de la Torre, E., Rossi, F. and Sagarra, M. (2018) Who benefits from HEIs engagement? An analysis of priority stakeholders and activity profiles of HEIs in the United Kingdom, Studies in Higher Education.