Energy Futures

The final finding sheet on this theme can be found at the bottom of the page.

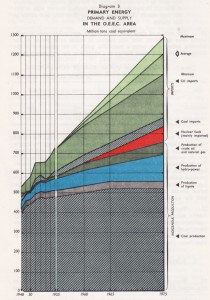

This research strand looks at the evolution of energy forecasts and visions of future demand. Contrary to popular wisdom, concerns over long-term energy shortages did not emerge with the 1973 oil crisis but had a long history. These reach back to concerns over a wood shortage in the seventeenth century and over peak coal in the Victorian era. The First World War revived debates over the longevity of coal supplies. After the Second World War, there were fears over stability, price controls and unhealthy dependence. In the half-century leading up to the ‘oil crisis’ national governments, international organizations, experts and consumers developed competing visions of what an energy future ‘might’ look like. These futures reflected current anxieties, imagining nebulous rates of change and acceleration that fluctuated between ideal and dystopian scenarios.

Our research places the creation of these ‘futures’ in their historical context. Who had the legitimacy and power to predict the future and shape energy policy for the next generation? How were questions of social and political order reflected within energy forecasts, as future visions came to embody larger political ideologies? This strand also examines the shifting body of ‘expertise’ and the changing place of more popular non-technical voices, including social movements and consumers, in authorised and unauthorised predictions of the future.

Time plays a critical role in energy consumption, because short- and long-term responses to energy were positioned within expanded temporal horizons. Not only will research consider how long-term projections affected everyday interactions with energy, it will also ask how short-term concerns manufactured long-term expectations. How stable were visions of the future in times of stress? During periods of shortage, when consumption habits were strongly moralized, were people more willing to challenge growth narratives incorporating alternative values for the future? Or does the twentieth century reveal a more uniform story, driven by acceleration and progress? Since semi-permanent structures (infrastructures, appliances and houses) installed patterns of usage for future generations, and often beyond the duration projected by the forecasts, we also need to investigate how future expectations of energy consumption were built into contemporary social spaces.

As part of its activity, the MCE project has contributed to the blog series ‘Experts: Past, Present and Future’, launched as a collaborative initiative by the MCE project, the Institute for Advanced Sustainability Studies (IASS) and the International Social Science Council (ISSC). The blog series includes a contribution by Frank Trentmann and Rebecca Wright ‘Energy Futures: Through the Looking Glass of “Experts”‘.

For more details, please see MCE Energy Future Finding Sheet.

MORE RESEARCH THEMES

Energy grids are not uniform. They have uneven social and cultural consequences that have affected energy use over time. In this theme we explore how grid developers have envisaged consumers in relation to the spatial formation of grids. And we ask how such visions have been connected to emerging domestic arrangements and shifting temporalities of demand. Our case studies include hydro-electric developments in Canada and Britain. The arrival of networks was uneven in different regions connecting consumers to a variety of material resources and infrastructures. This research theme investigates the range of connections forged by the arrival of grids and how these supported divergent methods of heating, cooking and lighting. Electrified and other energized spaces are shown to be the products of distinctive socio-political regimes that have evolved together with variable and dynamic consumer roles, expectations and routines.

'Communicating Material Cultures of Energy' project is a one-year public engagement funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council. The project explores various ways to improve the public communication of energy-related information and knowledge by bringing together 'energy communicators' across sectors and industries.

This toolkit takes stock of insights derived from contemporary communication practices, but it is also informed by recent research from the field of communication studies and the social science of energy. The five tools in this toolkit are designed to address core issues in energy communication. They are intended to be used as a set of adaptive methods to help communicators reflect on their communicative practices by using their own projects as examples. The exercises also offer somewhat unconventional methods through which to plan and review communication projects in order to reconsider the fundamental question of how to approach energy communication.

Black-outs, brown-outs and other disruptions of energy are today often associated with poor and developing countries, or as exceptional moments such as the Oil Crises of the 1970s. But energy shortages were a frequent feature also in advanced industrial societies and across the twentieth century. In this theme we are especially interested in the social, cultural and political histories of such disruptions and what they can tell us about a society’s attitudes to energy, ideas of ‘normality’ and fairness. Shortages tested a society’s ability to make do with less, and revealed norms and assumptions about fair shares and appropriate usage. In the case of electric networks, peak demand at particular times of day created a particular pressure. With selective case studies from Japan, Britain, and West and East Germany we examine the politics of disruption, paying particular attention to questions of distribution between different groups of consumers (from households to heavy industrial users) and to the politics of time. Disruptions reveal otherwise hidden dynamics and unspoken assumptions. They reveal people’s potential for flexibility and resilience at a time of stress. Such knowledge is vital to help us think about how we might deal with similar situations in the future.

What are the dynamics of change that lurk behind the trillions of KWhs that we in the developed world have come to treat as normal? The transition from wood and coal to coke, electricity, natural gas and oil varied immensely by country, region, class and building type. We examine people's values and practices as well as how new fuels were marketed. We look at how energy was gendered, made visible, priced and communicated, and at earlier efforts to modify behaviour and promote new technologies, with case studies in London, Burton-on-Trent, Saijo City (Japan) and Frankfurt am Main. These diverse energy worlds provide historical insights for energy transitions today and prospects for a more sustainable future.