In this second essay of a two-part series, philosopher Lisa Guenther explores what a meaningful memorial might be for the Prison for Women in Kingston, Ontario – a former site of prisoner abuse and psychiatric experimentation on vulnerable women.

Kingston, Ontario prides itself on being a place “where history and innovation thrive.” (link) But it’s not clear where the Kingston Prison for Women (P4W) fits into the city’s vision of its own past and future.

In my last blog post (link), I discussed the history of psychiatric abuse at P4W, as well as the decades of unheeded calls to close the prison due to unlivable conditions. Since the prison closed in 2000 and the surrounding walls were torn down in 2008, there has been little to distinguish the limestone building from other historic sites in the city. As one of my students said when we studied P4W in class, “I walk by that building every day on my way to campus, and I had no idea it was a prison.”

At the same time, hundreds of women across Canada walk through their lives with memories of their incarceration at P4W: memories of friendships and pain, death and survival, solidarity and despair.

This uneven distribution of memory and forgetting is not restricted to prisons. Kingston was the first capital of Canada (back when it was still a Province), and the first Prime Minister, Sir John A. MacDonald, grew up here. This part of Kingston’s history is well recognized and publicly celebrated with historic plaques, statues, and guided tours.

But the Indigenous history of the region is much less well-known to settlers, and there is remarkably little public acknowledgement of the complex relations between the Huron-Wendat, Mississauga, Algonquin, Mohawk and Oneida peoples in what the Huron and Mohawk called Ka’tarohkwi (link). Most settlers walk this ground every day, forgetting, neglecting, or refusing to acknowledge that it is stolen ground.

This normalization of settler denial has profound consequences for the psychic, social, and political life of settlers and Indigenous peoples in Canada – particularly in the criminal legal system. Indigenous people make up less than 5% of the Canadian population but over 26% of the federal prison population. Indigenous women are even more intensely hyper-incarcerated, accounting for almost 38% of the women in federal prisons (link). In provincial jails, the situation is even more extreme, especially in Prairie provinces like Saskatchewan where an astounding 76% of inmates are Indigenous (link). To put this somewhat differently, Indigenous people in Canada are 10 times more likely to be incarcerated than non-Indigenous people, and in Saskatchewan, they are 33 times more likely to be incarcerated (link).

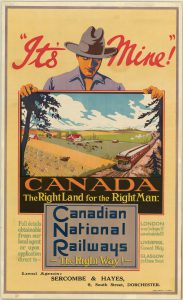

At the same time Indigenous people are hyper-incarcerated, police routinely fail to investigate the cases of missing and murdered Indigenous women, girls, trans, and two-spirit people (link), they harass Indigenous youth (link), and they actively endanger the lives of Indigenous people through so-called “starlight tours” (link) and other abusive practices, leading to outrageous levels of Indigenous deaths in custody (link). The 2016 killing of Colten Boushie, a young Cree man from the Red Pheasant First Nation, by Gerald Stanley, a white farmer, in Saskatchewan, and Stanley’s acquittal by an all-white jury in 2018, has sparked a nation-wide conversation about racism, settler colonialism, and the criminal legal system (link), forcing some settlers to confront the injustice of overt and covert genocidal policies and practices, and provoking others to grasp even more tightly to national myths of the right to settlement (link).

Colten Boushie’s uncle Alvin Baptiste raises an eagle’s wing as demonstrators gathered outside of the courthouse in North Battleford, Sask., on Saturday, February 10, 2018. The Canadian Press/Matt Smith

When settlers and Indigenous people walk the ground of North Battleford, Saskatchewan (link) – or when we walk past the former Prison for Women in Kingston/Ka’tarohkwi– it is not clear that we are in the same place, or even in the same time. And yet, these layers of space and time are somehow simultaneous, accessible from different perspectives and in various degrees of complexity, depending on the patience, attentiveness, and social location of the perceiver.

As a philosopher, I find inspiration in the practice of phenomenology for cultivating the patience and attentiveness that places like P4W demand. From a phenomenological perspective, the world is not merely a platform or container for autonomous human action. Rather, we exist as Being-in-the-world, wholly intervolved with the situation into which we are thrown, and constantly projecting possibilities for meaningful engagement or disengagement. For the most part, the meanings that we project are found ready-made, and we rarely take the time to reflect on their implications for our existence. (By “implications,” I don’t just mean consequences, I mean the way possibilities are folded or pleated into the way we walk, talk, think, and act.)

For many settlers, the ready-made meanings that organize our Being-in-the-world include: Canada is a nation of immigrants; I have a right to defend my property; development is progress; prisons and police keep us safe. These meanings are not just word sandwiches (although they are also that). They have a materiality that we often suppress or avoid, but that we sometimes feel in our bones or our guts, for better or for worse. When tourists flock to the former Kingston Penitentiary for a safe glimpse of the dark side (link), when settlers become frustrated with the “inconvenience” of Indigenous blockades (link), or when some of these same settlers begin to feel the transformative power of Indigenous resurgence movements like Idle No More (link) – these are the moments when the materiality of meaning hits us in a visceral way.

If we understand the world phenomenologically – as a palimpsest of meaningful-material layers, some of which get fused together over time, and others scraped away or buried to the point of oblivion – then we’re in a good position to see why the development of a former prison matters, not just for those who were incarcerated there, but for all of us who walk this ground. The shape of our relations with each other, with ourselves, and with the spatial and temporal dimensions of our world are at stake in this development.

If we understand the world phenomenologically…then we’re in a good position to see why the development of a former prison matters, not just for those who were incarcerated there, but for all of us who walk this ground.

The psychiatric abuse that Dorothy Proctor and twenty-two other women experienced at P4W continues to haunt the palimpsest of that place. So does the death, survival, love, and resistance of Indigenous women, who created the Strong Woman song at P4W, and who continue to sing it across Turtle Island (link).

Prison tours and boutique hotels in former prisons (link) exploit this haunting; they traffic in the frisson of terror and pleasure in forbidden places. Some former prisons are literally turned into Haunted Houses, with “attractions” such as “rioting zombie inmates” and “torturous experiments gone wrong” (link). But there are also ways of honouring the past and acknowledging its impact on the palimpsest of the present and the unfolding of possible futures. The P4W Memorial Collective is organizing a Healing Circle for Prisoners’ Justice Day (link) on August 10 (link). The group, of which I am a member, is led by women who were incarcerated at P4W. For years, they have been calling for a memorial garden on the former prison grounds, both to mourn the dead and to affirm and support the living (link). A memorial garden could become a powerful counterpoint to commercial development, whether or not this development is sensitive to the social history of the place.

But not all wounds can be healed. In “A Glossary of Haunting,” Eve Tuck and C. Ree write:

Haunting… is the relentless remembering and reminding that will not be appeased by settler society’s assurances of innocence and reconciliation. Haunting is both acute and general; individuals are haunted, but so are societies. The United States is permanently haunted by the slavery, genocide, and violence entwined in its first, present and future days. Haunting doesn’t hope to change people’s perceptions, nor does it hope for reconciliation. Haunting lies precisely in its refusal to stop. Alien (to settlers) and generative for (ghosts), this refusal to stop is its own form of resolving. For ghosts, the haunting is the resolving, it is not what needs to be resolved.

Haunting aims to wrong the wrongs, a confrontation that settler horror hopes to evade. (link)

This analysis of haunting marks the limit of even the most nuanced memorial project, and it also puts in question the naïve optimism of phenomenological attempts to see what has been obscured or distorted by settler colonialism. There are some things that even the most patient and attentive settler will not perceive, and perhaps should not perceive. The limits of settler perception do not get us off the hook; rather, they challenge us to become accomplices in Indigenous struggles for decolonization, and to commit to these struggles without knowing all the angles (link). To be haunted by colonization as a settler is to reckon with the past and present without assuming a happy ending of reconciliation, but also without accepting continued injustice.

As Tuck and Ree suggest, haunting does not imply a passive Indigenous subject reduced to a mere remnant of itself. Rather, haunting is an active practice of refusing to reconcile with colonial versions of justice, and affirming the power, creativity, and desire of Indigenous peoples. The future of decolonization and decarceration unfolds from this point of affirmative refusal.

Is it possible to both “wrong the wrongs” and heal the wounds of settler colonial carceral power? How would the process of working through the violence of the past and present affect the way settlers and Indigenous people relate to each other, to memory, and to possibility? How would it affect the ground we walk upon, not only in Ka’tarohkwi/Kingston, but also in London, England, and in other colonial metropoles?

Lisa Guenther is Queen’s National Scholar in Political Philosophy and Critical Prison Studies at Queen’s University in Kingston, Ontario. She is the author of Solitary Confinement: Social Death and its Afterlives (2013) and The Gift of the Other: Levinas and the Politics of Reproduction(2007), and co-editor of Death and Other Penalties: Philosophy in a Time of Mass Incarceration (2015) with Geoffrey Adelsberg and Scott Zeman. She is currently working on a book about incarceration, reproductive politics, and settler colonialism in Canada, Australia, and the United States. As a public philosopher, Guenther’s work has appeared in The New York Times, The Chronicle of Higher Education, Aeon, and CBC’s Ideas.