Guest Post

Guest Post

by Visiting Fellow Jessica Pearson-Patel

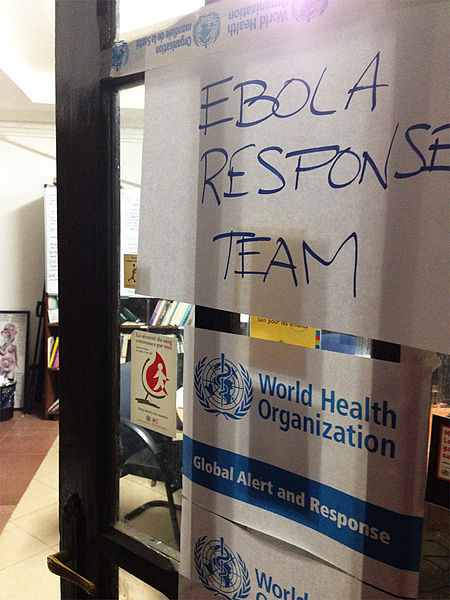

On May 9th, 2015, after months of fighting the outbreak, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared Liberia to be Ebola-free.[1] While this success demonstrates that both local public health services and international organizations did something right, the experience of the past year—along with the ongoing epidemic in Sierra Leone and Guinea—also demonstrate a number of important things they did wrong. A slow global response compounded a crisis sparked by poorly developed public health infrastructure—a legacy of European colonial rule in Africa—and a limited local understanding of the ins and outs of how the disease is transmitted. To date, the outbreak has resulted in over 11,000 deaths, and, even if fully eradicated, will have social and economic consequences for years to come.[2] The Ebola epidemic in West Africa reminds us that the role politics inevitably plays in shaping public health often has catastrophic consequences for the affected populations, something that historians of public health know all too well. In the case of Ebola, the political concerns that stopped the WHO from responding quickly and effectively to the outbreak resulted in thousands of deaths, often-inhumane quarantine measures, and, in certain cities, even widespread riots.

Criticism of the WHO’s inaction has focused on the decision to hold off on declaring the epidemic a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC), a declaration that comes with legally binding recommendations for the 194 member countries and can help to facilitate a coordinated global response. In internal emails and memos from June 2014, senior officials in the WHO cited fears of disrupting African economies, interfering with the pilgrimage of African Muslims to Mecca, and the pressure that such a declaration would have on the already-overextended WHO emergency response services, who were in the midst of dealing with a resurgence of polio and the spread of Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS).[3] (The resurgence of polio was declared a global health emergency in late spring, while MERS was not given this designation.) Dr. Michael Osterholm, a disease expert at the University of Minnesota, likened the decision to not declare the outbreak an international health emergency to “saying you don’t want to call the fire department because you’re afraid the trucks will create a disturbance in the neighborhood.”[4]

Several news sources registered shock at this apparently deliberate decision to delay the process of enacting emergency measures. After all, both the 1946 constitution of the WHO and its current mission statement suggest a staunch commitment to put the physical, social, and psychological needs of its global constituents first. Indeed, one of the founding principles, according to the constitution, was that “The enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of health is one of the fundamental rights of every human being without distinction of race, religion, political belief, economic or social condition.”[5] But as Dr. Thomas R. Frieden, the director of the Center for Disease Control, recently stated: “Too many times the technical is overruled by the political in W.H.O.”[6]

While contemporary media sources expressed surprise at the way politics shaped the Ebola response, for historians of global public health this story is a familiar one. In this particular context we can easily trace the entanglement of political imperatives and public health responses back to the earliest days of the World Health Organization’s involvement on the Africa continent. When the WHO was founded in 1946, it also created six regional offices to respond to varying health needs on the ground in different places. Of the six regional offices (Europe, the Americas, Western Pacific, Eastern Mediterranean, Southeast Asia, and Africa), the creation of the WHO Africa Office was the most rife with political drama and backroom diplomatic maneuverings. In colonial Africa, imperial powers feared that opening the door to the WHO would be akin to inviting international criticism of colonialism. Doctors and government officials worried that international health workers might use their work in Africa as a chance to spy on the inner-workings of their African empires. One French official wrote that a WHO Africa office would become a meeting ground for various kinds of “troublemakers: African, political, and medical.” He worried that by allowing the WHO to operate in Africa, they would be allowing outsiders a chance to create “a political climate unfavorable to French rule.”[7] Instead of thinking first about how to stop the spread of epidemic disease, these doctors and bureaucrats were thinking first about how to stop the spread of decolonization.

Despite their best diplomatic efforts, the French, British, and Belgians ultimately failed to keep the WHO out of Africa and a regional office was established in Brazzaville (French Congo) in the late 1940s. The decision to build the headquarters in Brazzaville was based on the idea that one should “keep one’s friends close and one’s enemies closer.” Colonial doctors thought that by setting up the office in the capital of French Equatorial Africa they would be able to more closely regulate the office’s programs. The first few years of the Africa office’s existence were not spent setting up the kinds of public health programs we have come to associate with the WHO. Instead, these years were plagued by bickering between WHO officials and colonial doctors about things like the creation of a public relations position, a role that the French administration claimed would allow the WHO to spread anti-colonial propaganda. It was not until the late 1950s, as European colonial rule in Africa was winding down, that the WHO was able to launch large-scale disease eradication campaigns in sub-Saharan Africa.

Both the current Ebola epidemic and this longer history of public health cooperation in Africa remind us that international health organizations like the WHO are often driven by broader local, regional, and international political contexts. As we consider the lessons that we can draw from the WHO’s failure to effectively respond to the current public health crisis brought on by the Ebola virus—and as the WHO considers reforms that will shape the way it responds to future public health emergencies—we should also consider the longer history of the way that politics have constrained the organization’s ability to execute its crucial mission.[8]

[1] WHO Statement: “The Ebola Outbreak in Liberia is Over,” 9 May 2015, http://www.who.int/mediacentre/news/statements/2015/liberia-ends-ebola/en/

[2] For current case counts, see the Center for Disease Control, 2014 Ebola Outbreak in West Africa – Case Counts, http://www.cdc.gov/vhf/ebola/outbreaks/2014-west-africa/case-counts.html

[3] “Bungling Ebola Documents,” The Associated Press, http://interactives.ap.org/specials/interactives/_documents/who-ebola/

[4] “Emails: UN Health Agency Resisted Declaring Ebola an Emergency,” The New York Times, 20 March 2015, http://www.nytimes.com/aponline/2015/03/20/world/ap-un-who-bungling-ebola.html

[5] WHO constitution, 1946. http://whqlibdoc.who.int/hist/official_records/constitution.pdf

[6] Sheri Fink, “W.H.O. Members Endorse Resolution to Improve Response to Health Emergencies,” New York Times, 25 January 2015.

[7] Archives de l’Institut de Médecine Tropicale du Service de Santé des Armées 238, Note pour Monsieur le Directeur des Affaires Politiques – 3ème Bureau, no. 6843, DSS/4, 4 Juil 1951, 1-2.

[8] For an outline of proposed WHO reforms in the wake of the Ebola outbreak, see “WHO reform: overview of reform implementation,” World Health Organization Executive Board, 136th Session, 19 December 2014, http://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/EB136/B136_7-en.pdf?ua=1