Blog-post author, Dr Matthew Coneys, Institute of Modern Languages Research, University of London.

Today’s travellers have access to a wide range of reading material to accompany them on visits to new places. I was reminded of this a few months ago when browsing online for a guidebook ahead of a trip to Rome. Among the well-known brands, my eye was drawn to the Wallpaper* City Guide: a slim volume, full of stylish photographs but rather light on text. The customer reviews were decidedly mixed. One of several consumers to give the guide a single star exclaimed: ‘the maps are useless, the travel information is non-existent and the information on the city is patchy to say the least!’ Many of the more positive reviewers highlighted the fact that the guide looked good on their bookshelf, suggesting that they bought into the philosophy of this ‘design-conscious guide for the discerning traveller’.

Pilgrims travelling to Rome in the late Middle Ages could also choose from an assortment of books to prepare them for and accompany them on their journey. The most popular guide of its day was the Latin Mirabilia Urbis Romae, written in the twelfth century and subsequently translated into most European vernaculars. The original Mirabilia was a largely secular guide to Rome’s monuments and history, but generations of scribes and printers updated it to include lists of the holy sites, as well as the indulgences that could be gained by visiting them. In the fifteenth century, pilgrims from all over Europe also produced their own guides to the city. One such text is the Englishman William Breywn’s Guide to Rome, discussed by Anthony Bale in another post on this blog. There are relatively few examples of these guides written in Italian, a fact that has been connected with the familiarity of Italian pilgrims with the eternal city.[1]

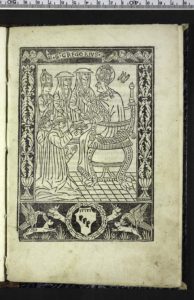

One exception to this trend is the Stazioni e indulgenze di Roma (Stations and Indulgences of Rome), written in the early 1490s by Giuliano Dati, a priest at the Basilica of St. John Lateran. Printed in Rome as a cheap pamphlet, the Stazioni offers a short guide to the Lenten station pilgrimage, in which pilgrims celebrated mass in a series of different churches over the course of Lent and Easter. Dati’s text is a useful reminder of the extent to which pilgrimage guides differed in this period. Opening with an invocation to the Muse, it is written in flowery ottava rima verse – a metre usually reserved for epic poetry and rarely associated with devotional texts. Somewhat surprisingly given the title of his work, Dati states in the opening stanzas that he will avoid any mention of indulgences so as not to ramble (‘non vorrei nel dire esser prolisso’).

Rather than the practical guide that it appears to be, the Stazioni in fact offers literary portrait of Rome and its churches based around the framework of the Lenten pilgrimage. In addition to hagiographic and historical information, it focusses in great detail on the architectural aesthetics of Rome’s churches. Dati’s interest in this area is attested in several of his later works, including his Aedificatio Romae, a treatise on the city’s architectural history. Although the inclusion of this kind of information in a pilgrimage account is far from unusual, the extent to which it dominates the text is surprising. Dati’s relegation of devotional matter is made particularly clear in his description of St Peter’s Basilica:

And know that, as well as miraculous indulgences,

This church contains many other things;

To tell of them all would make for a long sermon,

And too many words are boring.[1]

How then did the Stazioni’s author intend it to be read? Early in the text Dati declares that he will describe the holy sites in partial detail, leaving the pilgrim to follow the stations in full (‘ch’io narri parte delle cose sancte/poi segue la stazone tutte quante’). Those who purchased the Stazioni in Rome may therefore have read it alongside a more detailed guide, or used it to familiarize themselves with the station churches before embarking on their pilgrimage. Such a conclusion is supported by a comment in the description of Santa Maria Maggiore, where Dati offers a reason for the brevity of his work:

I have many more things to say

But I don’t want to bore my readers

Who will want to finish my work

So they can visit all the stations.[2]

Italian pilgrims may have read Dati’s pamphlet for a general overview of the Lenten pilgrimage, but it is also possible that it enjoyed a second function. Just as today we keep travel guides once we have returned home, lining them up on bookshelves to remind ourselves of our journeys (and others of our wordliness and sophistication), medieval pilgrims kept souvenirs of their experiences. These could be physical objects, such as the traditional pilgrim badges described in George Greenia’s post on this blog; but for many pilgrims the books that had accompanied them on their travels also retained a special value. The Stazioni may well have been written with this kind of afterlife in mind. A brief, accessible and enjoyable read, it serves first and foremost to create an image of Rome in the reader’s mind – one that they could revisit long after their pilgrimage, as Dati hints in the final stanzas of the poem:

When you have seen these things

And you return home

You will still see a church on a hill

Where St Peter was crucified.[3]

Was the Stazioni the Wallpaper* City Guide of its day? The comparison may not be perfect, but there is evidence to suggest that the fifteenth-century guidebook occupied a similar niche within the panoply of late medieval pilgrimage literature. Through further research into Dati’s pilgrim readers, focussing in particular on surviving copies of the Stazioni, I hope to shed further light on how and why this unusual text was read.

A digitized copy of the ‘Stazioni e indulgence di Roma’ can be accessed through the Biblioteca Europea di Informazione e Cultura (BEIC): http://www.beic.it/ (search ‘Giuliano Dati’).

Footnotes

[1] ‘E sappi che oltre a mirabil perdoni/in detta chiesa son di molte cose/che tutto dire sarian lungi sermoni/elle molte parole son noiose.’

[2] ‘E di molte altre cose harei da dire/ma non vorei le persone tediare/e vorren ch’ora la mia opra finire/volendo li stazon tutti trovare.’

[3] ‘Quando le dette cose vedut’ai/e che tu torni a casa stara fixo/a mezzo el monte una chiesa vedrai/dove fu Santo Pietro crocefisso.’

[1] Diana Webb, Medieval European Pilgrimage, c.700-c.1500 (Basingstoke: Palgrave, 2002), p.178.