Blog-post author Professor Anthony Bale, Birkbeck, University of London

(@RealMandeville)

The bibliographic remnants of medieval pilgrimage are often haphazardly or imprecisely catalogued; one can rarely rely on caalogues and handlists, without inspecting a book itself, to understand what the medieval source is. A good case in point is a book I recently inspected in the beautiful John Rylands Library, Manchester; from its record in the Index of Middle English Prose, I had thought that this manuscript (now Latin MS 228) might be a Jerusalem-bound pilgrim’s manuscript.

Latin MS 228 is a miscellany, and represents a very common kind of medieval manuscript, in which ‘useful information’ – legal documents, recipes, poetry, medical writing, and many other types of text – were gathered together. It is neither always apparent that a miscellany has an organising principle, nor is it often clear when the manuscript was organised. In the case of some manuscript miscellanies, their development seems to be organic, taking place over many years, and with many different owners adding – and deleting – contents, according to changes ideas of what was useful or desirable.

Latin MS 228 looks, on first sight, like it could be a pilgrim’s manuscript. It has a beautiful binding, dating from c. 1490-1525, in soft vellum. It would have been highly portable, and the back of the binding even has a flap in which to store loose leaves or other items. The binding is also important because it represents the moment at which someone put the book’s current contents together: that is, the moment of the book’s binding can reveal what was valued at that particular moment in time.

Moreover, Latin MS 228 contains two texts that relate to pilgrimage to Jerusalem, one in Latin and one in Middle English.

The Latin text (ff. 43v-44r) is headed ‘Itinerarium terre sancta’. In fact, it contains a few notes on the distances from Rome to Naples, from Venice to the Holy Land, from Jaffa (‘Portiaff’) to Jerusalem, from Jerusalem to Bethlehem, from Bethlehem to the River Jordan, and from Jerusalem to ‘Monte Synay’, Mt Sinai, and the tomb of St Katherine there. Then follows some notes on the relics and indulgences of Rome, and some historical notes on Saladin and the history of Jerusalem. There’s no evidence from this short Latin text that it was used by an actual pilgrim.

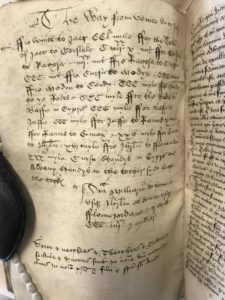

The Middle English text reads:

The way from venice unto Jaffe. Fro Venice to Jaer [Zadar] CCl mille ffor the town of Jaer to Corslake [Corcula] ciiiixx x mil ffor Corslake to Ragosa [Dubrovnik] iiiixx mil ffro Ragosa to Curfu CCC mil ffrom Curfu to Modyn [Methoni] CCC myle Ffrom Modyn to Candy [Crete] CCC myle ffrom Candy to þe Rodes [Rhodes] CCC myle ffor Baffe [Paphos] to Jaffe [Jaffa] CCC myle ffor Jaffe to Rames [Ramla] x myle ffor Rames to Emax [Emmaus] xxv myle ffor Emax to Jerusalem xvi myle from Jherusalem to Fflome iordan [River Jordan] xxxti myle. Curfu standys in Cypris [Cyprus] and Albany standys in the tother syde within the torke. Summa milliarium de venecia usque Jherusalem et deinde usque fflome jordane ii milia ccc iiiixx I millaria.

The Middle English text is perhaps more likely to represent an actual journey undertaken, suggested by the late-medieval toponyms and its greater detail. The mileages given here are not the same as in the Latin text, and the two texts are written in different hands. At the end of the Middle English itinerary a charm has been added.

So was Rylands Latin MS 288 a pilgrim’s book? Sadly, it’s impossible to say. We don’t know who its medieval owners were; the book has been much reorganised; and the Middle English text is on a single leaf – the other pages it was originally with have been cut out. On the reverse of this leaf is a short Latin extract, in the same hand as the itinerary, with an excerpt from the political prophecy of ‘Sixtus of Ireland’ (which includes the prophecy that the cities of Jerusalem and Acre will be retaken by a Christian prince).

However, the miscellany as a whole suggests that the pilgrimage texts were valued by whoever brought the book together in its current binding probably in the fifteenth century. What else did this person value? From the contents of his miscellany, we can discern an interest in medicine, law, and history. Some of the texts include:

- the fees and lands of the knights of Yorkshire

- a Middle English prose treatise on how to ‘undrestand what thi dreme betokenes’ using the letters of the psalter (f. 60r)

- the archers of each English shire, in French (f. 69r)

- medical recipes, including one to reduce swelling of the testicles through applying a paste made of boiled mint and pigeon-droppings

- several Middle English herbals, including a text on the uses of rosemary, which can ‘destroye all infirmites in manys body’ (f. 123v)

- a recipe for ‘bragot’ (f. 137v), a drink of ale warmed with honey and herbs

- a mass for ill cattle (f. 140r), which involves leading the animals into the barnyard, and having a priest with holy water say various gospel texts to the cattle as they turns their heads to the east.

As I am repeatedly discovering, it is very difficult securely to connect ‘pilgrims’ texts’ with actual pilgrimage or pilgrims. The journey to Jerusalem was clearly valued as a useful piece of information, something worth remembering, a mental route to return to over and over again, whether or not it had any practical application. We cannot say with any certainty that Rylands Latin MS 228 was ever used by a pilgrim; but we can be confident that the route to Jaffa and Jerusalem was on the mind of the book’s owner(s) in the late fifteenth or early sixteenth century.