Blog-post author Professor Ora Limor, The Open University of Israel

Dating the pilgrimage of Presbyter Jachintus

When did the Presbyter Jachintus make his pilgrimage to the holy places? We have in hand only one page of an only copy of the text he wrote to recount his visit, and it is of little use in answering this question. The surviving fragment holds only a description of Bethlehem, a mention of Rachel’s Tomb and part of a description of the Holy Sepulchre. This is a great pity, as the traveler had a sharp eye and was more interested in architectonic elements than any other known traveler of the Early Middle Ages. Deeply impressed by the monuments he had seen, the Presbyter Jachintus penned the only Holy Land itinerary from Iberia we possess after Egeria’s letter in the late fourth century.

Jachintus’ fragment, written in a Latin that reveals constructions close to Romance languages, was discovered by Zacarías García Villada in the library of the Cathedral of León. García Villada dated the fragment, after its paleographical data, to the tenth century. The date of the pilgrimage is more difficult to establish. At the beginning of his narration, Jachintus writes that the city of Bethlehem is destroyed (Civitatem Bethlem destructa est). García Villada, followed by Wilkinson in his translation of the text (Jerusalem Pilgrims before the Crusades, 1972, pp. 11, 123, 205), took this detail as key for dating it. García Villada believed that the destruction was caused either by the Persian or by the Muslim conquest (614, 637) and thus placed the visit sometime between the seventh and the tenth centuries. Wilkinson connected the destruction to an earthquake, perhaps the one that occurred in 746, and thus dated the pilgrimage to the eighth century. Both suggestions are problematic. It is well known that the Holy Land churches were rehabilitated soon after the Persian sack and that the Muslim conquest was not violent. As for the 746 earthquake, Theophanes writes that it caused destruction mainly in the Judean Desert, and Agapius mentions Tiberias, but none relate to Bethlehem in particular.

While these earlier works take Bethlehem as a guide, a new dating was suggested after the Holy Sepulchre description. Martin Biddle (1994, 1999) has argued that Jachintus is clearly describing the aedicule of the Holy Sepulchre as rebuilt in the eleventh century, in the course of the renovations following the destruction caused in 1009 by the Fatimid caliph Al-Hakim. The aedicule remained in this form for centuries, but its precise date of construction is unknown. It had to have been built before 1047, however, when the Persian traveler Naser-e Khosraw wrote about it in its new form.

Biddle recruits Jachintus to solve the problem. He suggests that Jachintus visited the church in the eleventh century, after the building of the aedicule, and that the León manuscript was copied later in that century. Following this notion, in his new edition of his Jerusalem Pilgrims before the Crusades (2002), Wilkinson changed the dating of the text to the eleventh century. Biddle’s suggestion is based on a single sentence at the end of the fragment, describing three windows (fenestre tres) on which the mass is celebrated. Biddle claims that these fenestre are the three windows in the marble covering the tomb, described by the Russian monk Daniel in 1106-1108, and thus exhibit the aedicule as constructed in the eleventh century. Nevertheless, as Biddle himself notes, the reference to the three fenestre comes at the end of the description of the aedicule, after the roof, and thus is out of sequence. If the three windows are indeed those known from Daniel’s treatise, they ought to have been mentioned within the aedicule and not in its exterior. As such, it is hard to know exactly what Jachintus is discussing. The dating of the text thus remains an open question.

References

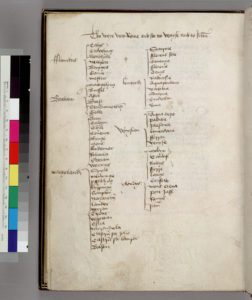

- Catedral de León, Codex 14, fol. 5.

- Zacarías García Villada, “Descripiones desconocidas de Tierra Santa en códices españoles”, Estudios Eclesiásticos 4 (1925), pp. 322-324.

- Julio Campos, “Otro Texto de Latin Medieval Hispano: El Presbítero Iachintus”, Helmantica: Revista de filología clásica y hebrea 8 (1957), pp. 77-89.

- John Wilkinson, Jerusalem Pilgrims before the Crusades (Jerusalem, 1978), pp. 11, 123, 205; John Wilkinson, Jerusalem Pilgrims before the Crusades (Warminster, 2002), pp. iii, 27, 404.

- Martin Biddle, “The Tomb of Christ: Sources, Methods and a New Approach” in Churches Built in Ancient Times: Recent Studies in Early Christian Archaeology, ed. Kenneth Painter. Series: Occasional Papers from the Society of Antiquaries of London, 16 (London, 1994), pp. 73-147, at p. 140, n. 14; See pp. 106-8.

- Martin Biddle, The Tomb of Christ (Stroud, 1999), pp. 85-88, 152, n. 61, 153, n. 68.

![Canterbury Cathedral Library (2013) [License: CC BY-SA 3.0]](http://www.bbk.ac.uk/pilgrimlibraries/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/Canterbury_Cathedral_-_library-150x150.jpg)