Blog-post author Professor Anthony Bale, Birkbeck, University of London

(@RealMandeville)

The Greek Orthodox Patriarchate in the Old City of Jerusalem is one of the most important resources for understanding the religious history of the Holy Land: in the Patriarchal Library are gathered the ancient manuscript treasures of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre and several other monasteries in the region.

-

The Monastery of the Holy Cross, Jerusalem. Photo: Anthony Bale

The Monastery of Mar Saba, near Bethlehem. Photo: Anthony Bale The Library’s main holdings comprise the Greek manuscripts previously held at Mar Saba near Bethlehem and the unique Greek and Georgian manuscript holdings of the Monastery of the Holy Cross (a Georgian foundation which is now a Greek house) in west Jerusalem.

In my work tracing the manuscripts held at the now-vanished medieval Franciscan monastery at Mount Zion, I had wondered if any pilgrims’ books might have found their way to a Greek monastery in the region. I was thus intrigued to find that amongst the Patriarchal Library’s holdings – which are overwhelmingly Greek and Georgian in origin – there is one Latin manuscript: MS Taphou 27.

Thanks to the assistance of Archbishop Aristarchos of Constantina, I was recently able to examine MS Taphou 27, to see if the book could be more securely associated with its medieval owners. What follows is very much a preliminary account of the manuscript, a starting-point for plotting the biography of a manuscript that seems to be ‘out of place’.

Inside the Greek Orthodox Patriarchate, Jerusalem. Photo: Anthony Bale Taphou 27 is a copy of Eutropius, a Classical chronicle dealing with Roman history. It was a very widely-read work, in both humanist circles and as a school text-book. Taphou 27 dates from the later fifteenth century, and includes some exceptionally beautiful illustrations and fine decorated lettering. The manuscript was almost certainly made in Italy, perhaps in Milan or Naples. It has a post-medieval binding, apparently British of c. 1800, and some of the book’s folios have been clipped.

There are a few clues in the book about its history and its journey from Italy to Jerusalem and the Greek Patriarchate. First, on the book’s first folio, are two Greek inscriptions, in different hands. The first, hard to decipher, suggests that the book was at Constantinople, at the Metochion of the Holy Sepulchre, by the year 1677. The second says that the book comes from “the belongings of Panayotis…which are useful to him” – it’s not clear exactly who or what this refers to. Over the coming months I hope to explore the possible meanings of these inscriptions with members of the Pilgrim Libraries project who are more familiar with Greek materials.

As Christopher Wright has shown, the manuscript was part of a large number of ancient books that were taken from the Ottoman empire to England, c. 1801, by Joseph Dacre Carlyle, Professor of Arabic at Cambridge, via the British embassy in Constantinople. Carlyle certainly took at least six books from Mar Saba, as a surviving receipt shows (now The National Archives, FO 78/81, f. 56r), and a number of manuscripts from the Metochion, lent by the Patriarch of Jerusalem Anthimos, who at that time resided in Constantinople. The manuscript passed to Carlyle’s sister Maria in 1804, and she retained it as a memento, having given the bulk of her brother’s collection to Lambeth Palace Library. The manuscript was returned by Maria Carlyle to the Greek Patriarchate around 1813, via the Patriarch Polycarpus. A Greek note on the front of MS Taphou 27 confirms the return of the book from England.

An important though previously overlooked aspect of MS Taphou 27 is that it contains the name of its scribe. On f. 138v, the final folio of the text, the scribe has written in his beautiful humanistic hand

I A C O B U S Laurentianus scripsit.

This Iacobus Laurentianus was the scribe of the whole volume. Laurentianus is by no means an unknown scribe: on the contrary, he was evidently a prestigious and highly-productive scribe in late fifteenth-century Italy, his work including commissions for the Aragonese court in Naples and the Sforza family in Milan. My preliminary research shows that a group of surviving Laurentianus manuscripts can be traced, now in collections around the world (given in a working hand-list below).

MS Taphou 27 can therefore be added to the known works written by Jacobus Laurentianus. It is not clear from the book however if it was written to commission – in my inspection of the book, I did not see any heraldic devices or similar evidence that would point to a medieval patron. As W. S. Monroe has shown, Laurentianus’ manuscripts were sometimes copied from printed texts, and MS Taphou 27 was likely copied from the printed edition of Eutropius (Rome, 1471); Laurentianus copied another manuscript of this text, now in the Escorial in Madrid.

This still doesn’t get us any closer to establishing how the book got from Italy to the Middle East, although the Greek inscriptions suggest that it was there by the mid-seventeenth century. The library of the Dukes of Aragon, based at Naples, shows that it held three books by Jacobus Laurentianus, including the copy of Eutropius, now in the Escorial, dedicated to Ferdinand/Ferrando of Aragon and, as Tammaro de Marinis shows, written at some point between 1471 and 1480. The Jerusalem manuscript is therefore almost certainly closely connected to this prestigious commission, although as I have not yet inspected the Escorial manuscript I cannot be sure of the relationship between the two. The Aragonese library at Naples was broken up in the later fifteenth century.

I am not at present in a position to make any firmer or larger conclusions about the book’s history but it is clear that Taphou 27 presents an intriguing piece of evidence in our attempts to understand the movement of books in the late medieval and early modern Eastern Mediterranean.

A provisional hand-list of manuscripts written by the scribe Jacobus Laurentianus

- Florence, Biblioteca Marucelliana MS ACB.IX.83

- Florence, Biblioteca Riccardiana MS 1569.s.15 (“Iacobus de s. Laurentio”)

- Jerusalem, Greek Orthodox Patriarchal Library MS Taphou 27

- Madrid, Escorial MS H.II.2; produced for the Aragonese court at Naples

- Naples, Biblioteca Nazionale di Napoli MS XI.AA.51

- Naples, Biblioteca Nazionale di Napoli MS XIII.C.76

- Paris, Bibliotheque National de France MS italien 1712, Vita de santi padri (1465); this manuscript seems to have been owned by Ippolita Sforza.

- Providence, Brown University, John Hay Library MS Latin Codex 9

- Rome, Biblioteca Casanatense, MS 112 (Laurentianus was the scribe of some sections)

- ?Venice, Biblioteca Marciana MS Lat. vi.245, Pliny the Elder

- Current whereabouts unknown: Diodorus Siculus (“Iacobus Laurentianus scripsit”), mentioned by Cherchi and de Robertis.

References and further reading

Paolo Cherchi and Teresa de Robertis, “Un inventario della biblioteca aragonese,” Italia medioevale e umanistica 33 (1990): 109-307

Lampadaridi, Anna, “Jerusalem, Library of the Patriarchate_1808-1827”, in Jerusalem, Patriarchy Library, Panaghiou Taphou 27 , Paris, IRHT, 2016 (Ædilis, Sites of scientific programs, 4) [Online] http: //www.libraria .fr / en / RIMG / jérusalem-librairie-du-patriarcat1808-1827

de Marinis, Tammaro, La biblioteca napoletana dei re d’Aragona (Milan, Hoepli, 1947-52) 4 vols.

Monroe, William S., “The Scribe, Iacobus Laurentianus, and the Copying of Printed Books in the Fifteenth Century”, paper presented at the Medieval Academy of America meeting, Vancouver 2008

Schadee, Hester. “The First Vernacular Caesar: Pier Candido Decembrio’s Translation for Inigo d’Avalos with Editions and Translations of Both Prologues.” Viator 46.1 (2015): 277-304.

Wright, Christopher, ‘Provenance and sub-collections’, in Christopher Wright, Maria Argyrou and Charalambos Dendrinos, A Descriptive Catalogue of the Greek Manuscript Collection of Lambeth Palace Library [Online] https://www.royalholloway.ac.uk/Hellenic-Institute/Research/LPL/Greek-MSS/Catalogue.pdf

I would like to thank the following for the help in drafting this blogpost: William S. Monroe, Marina Tompouri, Kostya Tsolakis, Nickiphoros Tsougarakis, and Archbishop Aristarchos of Constantina, Elder Secretary-General of the Greek Patriarchate, Jerusalem.

Inside the Greek Orthodox Patriarchate, Jerusalem. Photo: Anthony Bale Much Eaten by Mice: a fragmentary pilgrimage itinerary by Sir Gilbert Hay?

Dr Marianne O’Doherty Blog-post author, Dr Marianne O’Doherty, Associate Professor in English, University of Southampton, UK

Anthony Bale’s recent blog-post ‘A fifteenth-century itinerary through Europe to Jerusalem‘ points out that pilgrims’ itineraries in the Middle Ages can turn up in surprising places — sometimes in entirely unconnected books. I wanted to follow up with an interesting example found in the back of a copy of Walter Bower’s fifteenth-century Scotichronicon:

Cambridge, Corpus Christi College, MS 171b, fol. 368v. Described by M. R. James in 1912 as ‘much eaten by mice’ (p. 390). Image used with kind permission of the Master and Fellows of Corpus Christi College, Cambridge The handwriting of this scrap is particularly difficult to read, and made more so by the loss of much of the left-hand margin to hungry mice (a not uncommon medieval problem). But this is what makes it a useful text to test with a new, experimental, mapping and annotation tool: Recogito.

Recogito: A tool for transcription and annotation

Part of the Pelagios Linked Open Data infrastructure, the Recogito online platform – designed by Rainer Simon at the Austrian Institute of Technology –allows any registered user to upload a text or image (including maps) into a personal workspace. Users can then mark out place names in their text or map by selecting them with boxes, transcribe the place names, link them up to known past or present place names, and (for places with geocoordinates), quickly and easily visualize or plot them on a modern map:

Pick out a place name with a box and click to insert a transcription – here ‘Tangere’. Link to the place name and geocoordinates for Tangiers to enable mapping. Add comments (e.g. recording transcription uncertainties), and tags (e.g. categories such as ‘port’ or ‘holy site’ ) that you might want to use to categorise your data later. Here, I’ve numbered the place as point 4 in the itinerary. The system has a map visualizer, which makes it easy to see the places in the world to which a particular text refers and check transcriptions. Users can hover over a place to see the relevant excerpt of transcribed text, the transcription, and the place to which it’s mapped:

Granada in the text, transcription, and mapped. One particularly useful feature of Recogito, however, is its potential as a tool for collaboration. Recogito allows users to share documents privately with other users and collaborate on them, for instance to complete a partially-transcribed place name, or identify an obscure toponym:

An unidentified place name could be resolved through collaboration Once users have annotated, tagged, and mapped place references in Recogito, it’s easy to download the data created to analyse. For instance, one question this text excerpt raised was the extent of its reliance on the popular fourteenth-century account Mandeville’s Travels. The itinerary talks about a miraculous image of the Virgin Mary at ‘Sardonade’ (Saidnaya) that Mandeville describes in detail (p. 58). However, when both texts are ‘mapped’ (here using the free online Carto DB platform) it becomes clear that there is not much overlap beyond this one distinctive element.

Places mentioned in Mandeville in blue and those on the Hay itinerary in orange. Accessed 8 May 2017. The Corpus Christi 171b itinerary may, perhaps, be a version of the kind of splicing together of sources about pilgrimage– possibly including personal experience – with Mandeville that Anthony Bale has recently observed in other fifteenth- and sixteenth-century sources (Bale 2016).

Working on itineraries using Recogito opens up new possibilities for tracing trends over time. It might allow to compare itineraries easily, using one to shed light on another. In the longer term, it’s planned that the Recogito infrastructure will enable this kind of work by allowing for searching and comparison of place references across a wide range of sources.

Whose itinerary is it anyway?

But there are still some unanswered questions. Who wrote these strange scraps of itinerary? Are they records of the writer’s personal experience, things he has heard, things read, or a mixture of all of these?

We can at least identify the writer of these notes, because an accident of the book’s history means he has left us his name. At some point in MS 171a’s early history, somebody cut out half one of its empty leaves (folio xix, MS 171a), presumably to use the purloined paper for other purposes. This has precipitated a ‘book curse’ directed at the thief, written on the remainder of the damaged folio in the same messy handwriting as the itinerary notes. The ‘curser’ signs himself ‘Gilbert ye Hayes’ (fol. xixv).

Gilbert was a fairly common name among the Hays, an important Scottish family, in the later Middle Ages (Brown, p. 21), yet we can be fairly sure who this one was. As Watt noted in his edition of the Scotichronicon (IX: 50-53), the same ‘large, untidy’ hand is responsible for additions and corrections to what the Chronicle has to say about a Gilbert Hay active France in the early fifteenth century, where he became chamberlain to, and was knighted by, Charles VII. This Sir Gilbert (d. 1465) can in turn be firmly identified as the author of a number of mid-fifteenth-century writings, including a verse Buik of King Alexander the Conqueror.

Did Sir Gilbert embark on any of the journeys that he sketches out in this note? The fragment provides no clue. But another, longer itinerary fragment of Gilbert’s in the same book suggests that Hay collected details of journeys he had not himself undertaken. It features an itinerary from Rome that stretches as far east as the Empire of the Great Khan of Cathay (MS 171b, fol. 370r), but this empire had fallen nearly a century before Sir Gilbert wrote. Hay’s biographers have, however, noted gaps in his biography in the late 1440s and early 1450s, and after 1460 (ODNB; Brown, p. 20). Might Sir Gilbert, perhaps, have undertaken or contemplated a Jerusalem pilgrimage during any of these periods, prompting him to note down this pilgrim’s itinerary?

References:

- —–, Pelagios Commons. Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. Online Resource. Accessed 8 May 2017

- A. Bale, ‘A fifteenth-century itinerary through Europe to Jerusalem‘. Pilgrim Libraries: books & reading on the medieval routes to Rome & Jerusalem. 20 April 2017. Online resources. Accessed 8 May 2017

- A. Bale, ‘“ut legi”: Sir John Mandeville’s Audience and Three Late Medieval English Travelers to Italy and Jerusalem’, Studies in the Age of Chaucer, 38 (2016), 201-37

- W. Bower, Scotichronicon, ed. D. E. R. Watt and others, new edn, 9 vols. (Aberdeen: Aberdeen University Press, 1987–98)

- M. Brown, ‘The stock that I am a branch of”: patrons and kin of Gilbert Hay’, in Fresche fontanis: Studies in the Culture of Medieval and Early Modern Scotland, ed. by Janet Hadley Williams and Derrick McClure (Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2013), pp. 17-30

- C. Edington, ‘Hay, Sir Gilbert (b. c.1397, d. after 1465)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004). Online resources. Accessed 8 May 2017

- M. R. James, A Descriptive Catalogue of the Manuscripts in the Library of Corpus Christi College, Cambridge, 2 vols. (Cambridge: Cambridge: University Press, 1912)

- J. Mandeville, The Book of Marvels and Travels, ed. by Anthony Bale (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012)

- N. Wilkins, Catalogue des manuscrits français de la bibliothèque Parker. (Cambridge: Parker Library Publications, Corpus Christi College, 1993

- T. Porck, ‘Paws, Pee and Mice: Cats among Medieval Manuscripts’. Turning Over a New Leaf: Manuscript Innovation in the Twelfth Century. Institute for Cultural Disciplines, Universiteit Leiden, NL. 22 February 2014. Online resources. Accessed 8 May 2017

- R. Simon, Recogito: Linked Data annotation without the pointy brackets Austrian Institute of Technology. Online resource. Accessed 8 May 2017

- J. H. Stevenson, ed., Gilbert of the Haye’s prose manuscript (AD 1456), 2 vols., STS, 44, 62 (1901–14)

Travelers’ Texts: pilgrims and their textual accessories

Professor George Greenia Blog-post author, George Greenia, Professor Emeritus, College of William & Mary, US

Medieval pilgrim badges were among the most common souvenirs brought home from visits to European shrine sites. They were worn at eye level on hats and shoulder capes, sewn into prayer books, and adorned pilgrim bodies laid in their graves. Today’s trekkers to Santiago mark their backpacks with the traditional scallop shell and purchase endless variations of that icon emblazoned on kitchen tiles, refrigerator magnets, jewelry and even their hiking socks. Insignia are public announcements, billboards for piety or bragging read at a glance.

Other historic pilgrim accessories appeal to literacy at least as a cultic gesture. Many short texts were never read at all. They simply served as visual scripts for their bearers’ good intentions. Pilgrims – or any travelers wishing to make their journey sacred – could take along something written even if only as an amulet. Here are a small selection of such objects from various historical moments and contexts.

The Orthodox Crescent arcs from northern Egypt to Finland with numerous shrine sites along that vast geographical span. They are normally working monasteries with Mount Athos island in Greece the best known cluster of religious communities in one of the most spectacular settings. Monastics themselves often become pilgrims who journey to venerate the icons and sacred images that compete for honor with bodily relics and tombs. Professed religious often carry portable devotional objects with them, sometimes just for the imagery and sometimes with textual reminders of the prayers they may recite along the way. Some artifacts that include writing with their imagery help prompt live storytelling of miraculous events or episodes from scripture.

Wearable Byzantine case, 19th cent.? 4.5 x 4.5 cm, chain 24 cm, metal, private collection, photo © George Greenia. Wearable Byzantine case, 19th cent.? 4.5 x 4.5 cm, chain 24 cm, metal, private collection, photo © George Greenia. This small metal box has a short chain, so the case could hang on a vendor’s rack, the traveler’s kit, or be left as a votive offering at a shrine site. A sliding metal tab along the top seals an inner compartment which could contain a personal relic, blessed oils preserved in wax, or a small packet of written material. The writing on the outside of this case simply names the saints on either side.

Byzantine triptych, 19th cent.?, 9 x 10.5 cm, metal, private collection, photos © George Greenia. Byzantine triptych, 19th cent.?, 9 x 10.5 cm, metal, private collection, photos © George Greenia. The palm-size metal triptych is also scaled for private devotions on a home altar or especially for travelers because of its minimal weight and because it folds up so readily to protect the devotional surface. The writing is limited to the names of the figures or the scenes depicting the life and miracles of St. Nicholas.

Pilgrim flask representing St. Menas with two camels. From the area of Alexandria, Egypt. Common from 6th-7th cent. 14.5 cm x 10 cm; depth 3.2 cm, clay, Louvre, Creative Commons. Pilgrim flask representing St. Menas with two camels. From the area of Alexandria, Egypt. Common from 6th-7th cent., clay, private collection, 14 x 7 cm, photo © George Greenia. This small vessel is a pilgrim’s flask destined to contain water, oil or sand from a sacred site. St. Menas flanked by camels was the icon for the saint’s shrine west of Alexandria where pilgrims took oil from the sanctuary lamps to carry home with them. Flasks were formed from clay disks pressed into molds to capture images and script. These disks were sealed together and loop handles pasted on. The interior volume is irrelevant. Just possessing some of the material substance gathered at the shrine site was enough for travelers and proof of the completion of their mission. Those on a quest are the first beneficiaries of the power of their souvenirs but they function as a boon for their home communities as well. The first image shows a well preserved, museum-quality St. Menas flask but thousands more survive as travel-fatigued items in private collections, as in the second image.

The Christian West and Orthodox East in general have rates of lay literacy higher than in the Middle East, especially in liturgical languages. They also boast a vast range of iconography in the plastic arts. Medieval scriptoria flourished in administrative centers, both lay and ecclesiastical, increasingly around universities and for a growing late-medieval lay market as well. Their pilgrim sojourners came from every social class lay and professed, and they collected souvenirs such as ampules of water and oil, pilgrim badges, carvings and icons.

Ethiopian prayer scroll, late 19th cent., goat skin, 8 cm wide by up to a meter in length, prepared for named woman Wälättä Maryam: http://dynamicafrica.tumblr.com Ethiopian travelers represent a distinct class of pilgrim. Like their Orthodox counterparts, they retain a unique liturgical language, in this case written in Ge’ez, the ritual idiom of Christian Ethiopia much like Old Church Slavonic or antique forms of Greek for portions of the East, or Latin for the Christian West. Mastery of Ge’ez remains confined to a literate priestly elite. Ethiopian religious books don’t just contain sacred texts, they are sacred objects in themselves, and their images are strikingly apotropaic: they produce and induce the spiritual realities they illustrate. The portraits of Christ, Mary and the saints and especially the endlessly repeated angels’ eyes make those forces effective in the real world.

Within the Ethiopian catchment regions, religious books are routinely hand crafted by individual monks, not the output of organized shops. Individual monks produced written texts as a sacred craft, rarely as an industry increasingly dominated by laymen as in the West. Their books commonly stay in the possession of monks who use them for daily prayer and carry them on their errands and journeys. With literacy more confined to a monastic caste in Ethiopia and working with a smaller repertoire of iconography, devotional objects on goatskins and as worked brass are scaled down in size.

Lay people tend to collect “prayer scrolls” carried as amulets. Many of these scrolls are talismans whose prayers address specific needs and protect against disease. The person who commissioned the manuscript is as often as not a named woman and the prayers she requested include petitions concerning feminine ailments or to ward off dangers like the evil eye, or a prayer for catching demons in Solomon’s Net. These women wanted written prayers even though they could not read them and wore them under their clothing and in contact with their flesh.

Unfairly called “magic scrolls,” they are simply invocations to God and the saints for shelter from harm. The illustration shows a scroll containing the following prayers: “(1) Prayer of Susenyos, (2) Prayer for the “expulsion” of disease and the demon Shotalay”, (3) prayer against the evil eye, (4) prayer against rheumatism and sciatica, (5) prayers against haemorrhage, (5) another prayer against demon Shotalay, (6) prayer against Zar Wellaj.” (Reed, 2011)

Some scrolls were sewn tight in leather pouches, never to be opened again. The fact that no one would ever read these prayers aloud did not trouble their owners who themselves became “mobile shrines” as they carried sacred objects about on their persons. The texts on these inaccessible strips of animal hide were placed in the sight of God alone and entrusted to His readership. These believers converted their textual accessories into moveable shrines and made of themselves pilgrims in a self-referential way, carrying the sacred forward to sanctify all the places they visited and worked, accompanied by the transcendent inscribed on parchment scrolls nestled next to their skin.

Yemeni devotional case for prayers or sura of the Qur’an. Mid-20th cent., copper and silver alloy with paste glass “rubies,” 7.5 cm wide x 11 cm tall with bells, metal chain approx. 30 cm in length, photo © George Greenia. Finally, an example from Yemen. This rectangular case is similar to the first object but comes from the Islamic tradition. It bears passing resemblance to the Jewish mezuzah which is affixed to the doorpost of a home and never travels at all. Composed of a handcrafted alloy of silver and copper set with glass “rubies,” this Yemeni case’s bells suggest movement, either processional or on pilgrimage. It too is outfitted with a chain for personal wear or placement in a devotional setting. Although now completely sealed, the box has a hollow interior for a short passage from the Qur’an.

Reference

‘What Real Clerical Spell Scrolls Look Like. Ge’ez and Amharic Examples‘ by R. D Reed, in Cyclopeatron. Friday 17 June 2011. Web resource, accessed 17 May 2017.

Building imagined pilgrimage experiences and pilgrim libraries in the medieval world

Phil Booth Blog-post author, Phil Booth, Associate Lecturer at Lancaster University, UK

Creating tools of contemplation and remembrance

When talking about Christian pilgrimage in the medieval period, there exists a tendency to divide pilgrimage into geographic types: the local, the national, the transnational and the international (for example). Each of these “types” of pilgrimage exhibit different qualities and were performed for different reasons at different times. The motivation, for example, for undertaking a pilgrimage to Jerusalem might be vastly different from undertaking a pilgrimage to any number of local shrines which existed in Europe (and elsewhere) at this time. Yet one thing these “types” had/have in common was a belief in the benefit that could be derived from movement towards, and interaction with, a sacred space.

c15 image produced to accompany a translation of Burchard of Mt Sion’s ‘Descriptio Terrae Sanctae’. Images like this were crucial for facilitating imagined or virtual pilgrimage experiences. (Source: Wikimedia Commons) Increasingly, however, historians have recognised that pilgrimage did not require any sort of movement or travel at all; that there existed, in medieval Europe, a belief in what has been variously described as virtual, imagined or armchair pilgrimage. Simply put, people imagined themselves going to or seeing specific holy places believing they would benefit from the exercise. Paramount in facilitating an imagined pilgrimage experience were books, or other material objects, that could evoke an image of sacred space and associated events. Through ritual movements, physical touching of material objects, and simple contemplation an individual could experience a pilgrimage from the comforts of their own homes (or convent/monastery as was usually the case).

In this regard it is interesting to note that when pilgrims who wrote accounts of their pilgrimages sat down to do so they often express a very clear appreciation that their accounts of pilgrimage could be used in such a way. They were to be used as tools of contemplation and remembrance. Indeed, for many it was this very aspect of medieval spirituality which inspired them to record their pilgrimage experiences for posterity. Some examples.

John of Würzburg who travelled to the Holy Land in around 1160 stated:

I believe that this description will be valuable to you [i.e. Dietrich, the individual to whom the account is written] if … you come to everything which I have described and see them [i.e. the holy places] physically … But if you happen not to go [to the Holy Land] and you are not going physically to see them, you will still have a greater love of them and their holiness by reading this book and thinking about it.

The best example of these trends from the twelfth and thirteenth centuries occurs in the account of Burchard of Mount Sion, a Dominican friar who spent several years in the Holy Land in the late-thirteenth century. The introduction of his account is replete with references to the imagined experiences which pilgrimage to the Holy Land could provoke. Most noteworthy for our present considerations, however, is his statement that:

Seeing, however, that some people are affected by a desire to picture for themselves in some degree at least those things that they are unable to look upon face to face and wanting to satisfy their wish as far as I can, I have … described … that land [i.e the Holy Land] through which I have frequently passed.

These pilgrims were clearly producing these accounts to facilitate an imagined or remembered experience once back at home. However, it should be noted that this was not a uniquely “Catholic European” preoccupation. Daniel, a Russian abbot, and therefore an Orthodox Christian, who travelled to the Holy Land between 1106 and 1107, also wanted his account to enable people to think on or remember the holy places:

… for the love of these holy places I have set down everything which I saw with my own eyes, so that what God gave me, an unworthy man, to see may not be forgotten … I have written this for the faithful. For if anyone hearing about these holy places should grieve in his soul and in his thoughts for these holy places, he shall receive the same reward from God as those who shall have travelled to the holy places.

c14 depiction of Xuanzang returning from India laden with Buddhist texts. (Source: Wikimedia Commons) Even more fascinating is that it does not seem to have been a uniquely Christian preoccupation either. Other religious cultures in the Medieval world expressed and practiced their spirituality in diverse ways. Pilgrimage, whilst possessing many universal qualities, was and still is performed in different ways, by different peoples, groups and religions. And those cultures which wrote about pilgrimage did so for sometimes different reasons. Nevertheless, when reading the Record of the Inner Law sent home from the South Sea, composed by the Buddhist monk Yijing, who travelled to India from China between 671 and 695, we read:

My life may sink with the setting sun this day, still I work to do something worthy of the promotion of the Law; … If you read this record of mine, you may, without moving one step, travel in all five countries of India, and before you spend a minute you may become a mirror of the dark path for a thousand ages to come.

While this is the only such reference of which I am aware of, what it shows is that imagined pilgrimage was not something peculiar to Christians or Europe. Furthermore, the experiences of these remarkable Buddhist pilgrims were intrinsically bound up with textual records. They travelled from China to India in the hope of recovering the original texts of Buddhism and they themselves were inspired to produce texts to help individuals become better Buddhists. They were also interested in building libraries of their own. Xuanzang who travelled in the seventh century (and whose travel account influenced Yijing’s own journeys) brought back to China some 657 Buddhist texts, Yijing himself some 400 texts, which were translated into Chinese and formed new libraries of knowledge connected to pilgrimage and Buddhism. The pilgrimages of the likes of Faxian, Yijing and Xuanzang were all about libraries, reading, the betterment of oneself and imagined journeys.

Overall it demonstrates the important link that existed between pilgrimage, text and imagination in multiple “medieval” cultures.

A fifteenth-century itinerary through Europe to Jerusalem

Professor Anthony Bale Blog-post author Professor Anthony Bale, Birkbeck, University of London UK. @RealMandeville

The Weye Unto Rome

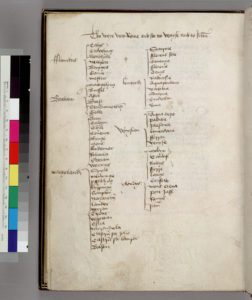

and Soo to Venyse and to JerusalemItineraries appear in surprising places in medieval manuscripts, often apparently out of context. One such example appears in San Marino, Henry E. Huntington Library MS EL 26.A.13 (f. 115v), a compilation of Middle English poetry, mostly by Lydgate and Hoccleve. The itinerary was added to the book but at more or less the same time as the rest of the book was written – that is, in the later fifteenth century. Thus the itinerary has no direct connection with the other texts in the book, although several of the texts reveal an interest in wisdom literature, translation, and proto-humanism.

This itinerary runs from the English-held town of Calais in northern France to Jerusalem. It is not in the correct order, and so possibly represents a remembered journey, or one excerpted from a written account but never undertaken (for instance, to go from Ghent to Mechelen via Maastricht would be a significant detour).

The manuscript was inscribed with the names of the scribe John Shirley (d. 1456), his wife Margeret, her sister Beatrice, and Beatrice’s husband Avery Cornburgh (d. 1487).

Ownership inscription of John and Margaret Shirley and Beatrice Cornburgh. San Marino, Henry E. Huntington Library MS EL 26.A.13, f. (v)v. http://www.digital-scriptorium.org Cornburgh, originally from Cornwall and later of Gooshayes (Essex), was yeoman at the Lancastrian, Yorkist, and Tudor courts and a man of considerable power.[1] Cornburgh is not known to have travelled as a pilgrim but he did have a number of important maritime connections, and his nautical and mercantile expertise was valued at the royal court. In the 1460s Cornburgh was responsible for buying and provisioning several royal ships, he was appointed a sea captain in 1474, and seems to have taken a leading part in various expeditions, to Scotland, Germany, and France. Cornburgh was closely connected to John Howard, first Duke of Norfolk (d. 1485), one of the major ship-owners of fifteenth-century England.[2] Moreover, Cornburgh’s stepson, Thomas Oxeney, was appointed havener (keeper of the ports) in Cornwall and Devon, a role which would have brought him into contact with many foreign merchants and travellers. This is then a plausible context in which a traveler’s itinerary might have been added to an otherwise literary manuscript.

Whether or not the itinerary represents a real journey or an imaginative exercise remains moot: but it shows a curiosity and a knowledge about the world beyond England and the internationalism of late medieval English readers.

Itinerary from Calais to Jerusalem,San Marino, Henry E. Huntington Library MS EL 26.A.13 (f. 115v). http://www.digital-scriptorium.org High quality images of the itinerary can be viewed in the manuscript here. I have transcribed the itinerary below, and supplied modern place-names where I’m confident about them. If you have suggestions about any of my queries – where is the island of ‘Ferre’ in the Aegean? Is ‘Mons Etena’ Mount Etna, but out of place? – then please do contact me.

The Weye Unto Rome and Soo to Venyse and to Jerusalem, from San Marino, Henry E. Huntington Library MS EL 26 A 13 (Part I), f. 115v:

Fflandris: Calys Gravelyng

Donckyrke

Newport

Brugges

Gaunt

Mastric

Braban: Mawghlyng

Brossil

Ascot

Deest

Tendurmowth

Golke

Ducheland: Acon

Coleyne

Gonne

Conence

Bynge

Mens

Andernac

Pobarba

Oderam

Wormys

Spyre

Menlynge

Jes[?]helyng

Kyppinge

Kemptoun

Nazareth

Landec

Myran

Trent

Venowan

Ostia

Myrendula

Castrum sancti Johannys

Castrum sancti laurens

Bolsen

Lombard: Scarpore

Fllorens Sole

Bononya

fflorens

Cenys

Radocofye

Aquapendent

Viterbia

Sutrina

Turbaken

Roma

Venysian: Aqua depo

Padwa

Plesance

Bonecovent

Fferrar

Venyse

Ylondys: Modyn

Candif

Roodys

fferre

Lango

Corfew

Mons etena

Port Jaff

Ramys

Jerusalem

Calais Gravelines

Dunkirk

Nieuwpoort

Bruges

Ghent

Maastricht

Mechelen

Brussels

Aarschot

Diest

Dendermonde

Juelich

Aachen

Koeln

Bonn

Koblenz

Bingen

Mainz

Andernach

Boppard

Odernheim

Worms

Speyer

Memmingen

Geislingen

Goeppingen

Kempten

Nassereith

Landeck

Murano

Trento

Verona

Ostiglia

Mirandola

San Giovanni in Persiceto

Borgo San Lorenzo

Bolzano

Scarperia

Firenzuola

Bologna

Florence

Siena

Radicofani

Acquapendente

Viterbo

Sutri

Baccano

Rome

Acqua di Po [River Po?]

Padua

Piacenza

Buonconvento

Ferrara

Venice

Methoni

Crete

Rhodes

? [Paros?]

Kos

Corfu

Mount Etna?

Jaffa

Ramla

Jerusalem

[1] See. R. E. Stansfield, ‘A Duchy officer and a gentleman: The career connections of Avery Cornburgh (d.1487)’, Cornish Studies 19 (2011), 9-35. Cornburgh was married to Beatrice Oxeney (d. 1501), daughter of the wealthy London wool merchant and grocer William Lynne (d. 1421).