Blog-post author Professor Anthony Bale, Birkbeck, University of London UK. @RealMandeville

The Weye Unto Rome

and Soo to Venyse and to Jerusalem

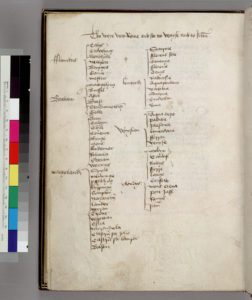

Itineraries appear in surprising places in medieval manuscripts, often apparently out of context. One such example appears in San Marino, Henry E. Huntington Library MS EL 26.A.13 (f. 115v), a compilation of Middle English poetry, mostly by Lydgate and Hoccleve. The itinerary was added to the book but at more or less the same time as the rest of the book was written – that is, in the later fifteenth century. Thus the itinerary has no direct connection with the other texts in the book, although several of the texts reveal an interest in wisdom literature, translation, and proto-humanism.

This itinerary runs from the English-held town of Calais in northern France to Jerusalem. It is not in the correct order, and so possibly represents a remembered journey, or one excerpted from a written account but never undertaken (for instance, to go from Ghent to Mechelen via Maastricht would be a significant detour).

The manuscript was inscribed with the names of the scribe John Shirley (d. 1456), his wife Margeret, her sister Beatrice, and Beatrice’s husband Avery Cornburgh (d. 1487).

Cornburgh, originally from Cornwall and later of Gooshayes (Essex), was yeoman at the Lancastrian, Yorkist, and Tudor courts and a man of considerable power.[1] Cornburgh is not known to have travelled as a pilgrim but he did have a number of important maritime connections, and his nautical and mercantile expertise was valued at the royal court. In the 1460s Cornburgh was responsible for buying and provisioning several royal ships, he was appointed a sea captain in 1474, and seems to have taken a leading part in various expeditions, to Scotland, Germany, and France. Cornburgh was closely connected to John Howard, first Duke of Norfolk (d. 1485), one of the major ship-owners of fifteenth-century England.[2] Moreover, Cornburgh’s stepson, Thomas Oxeney, was appointed havener (keeper of the ports) in Cornwall and Devon, a role which would have brought him into contact with many foreign merchants and travellers. This is then a plausible context in which a traveler’s itinerary might have been added to an otherwise literary manuscript.

Whether or not the itinerary represents a real journey or an imaginative exercise remains moot: but it shows a curiosity and a knowledge about the world beyond England and the internationalism of late medieval English readers.

High quality images of the itinerary can be viewed in the manuscript here. I have transcribed the itinerary below, and supplied modern place-names where I’m confident about them. If you have suggestions about any of my queries – where is the island of ‘Ferre’ in the Aegean? Is ‘Mons Etena’ Mount Etna, but out of place? – then please do contact me.

The Weye Unto Rome and Soo to Venyse and to Jerusalem, from San Marino, Henry E. Huntington Library MS EL 26 A 13 (Part I), f. 115v:

| Fflandris: Calys

Gravelyng Donckyrke Newport Brugges Gaunt Mastric

Braban: Mawghlyng Brossil Ascot Deest Tendurmowth Golke

Ducheland: Acon Coleyne Gonne Conence Bynge Mens Andernac Pobarba Oderam Wormys Spyre Menlynge Jes[?]helyng Kyppinge Kemptoun Nazareth Landec Myran Trent Venowan Ostia Myrendula Castrum sancti Johannys Castrum sancti laurens Bolsen

Lombard: Scarpore Fllorens Sole Bononya fflorens Cenys Radocofye Aquapendent Viterbia Sutrina Turbaken Roma

Venysian: Aqua depo Padwa Plesance Bonecovent Fferrar Venyse

Ylondys: Modyn Candif Roodys fferre Lango Corfew Mons etena Port Jaff Ramys Jerusalem |

Calais

Gravelines Dunkirk Nieuwpoort Bruges Ghent Maastricht

Mechelen Brussels Aarschot Diest Dendermonde Juelich

Aachen Koeln Bonn Koblenz Bingen Mainz Andernach Boppard Odernheim Worms Speyer Memmingen Geislingen Goeppingen Kempten Nassereith Landeck Murano Trento Verona Ostiglia Mirandola San Giovanni in Persiceto Borgo San Lorenzo Bolzano

Scarperia Firenzuola Bologna Florence Siena Radicofani Acquapendente Viterbo Sutri Baccano Rome

Acqua di Po [River Po?] Padua Piacenza Buonconvento Ferrara Venice

Methoni Crete Rhodes ? [Paros?] Kos Corfu Mount Etna? Jaffa Ramla Jerusalem |

[1] See. R. E. Stansfield, ‘A Duchy officer and a gentleman: The career connections of Avery Cornburgh (d.1487)’, Cornish Studies 19 (2011), 9-35. Cornburgh was married to Beatrice Oxeney (d. 1501), daughter of the wealthy London wool merchant and grocer William Lynne (d. 1421).

![Canterbury Cathedral Library (2013) [License: CC BY-SA 3.0]](http://www.bbk.ac.uk/pilgrimlibraries/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/Canterbury_Cathedral_-_library-150x150.jpg)