When the Senate Intelligence Committee released their report on the CIA’s use of ‘enhanced interrogation’ techniques, Dick Cheney was quick to respond. (The report, Committee Study of the Central Intelligence Agency’s Detention and Interrogation Program, can be downloaded in full here) On NBC’s Meet the Press the former Vice President kicked against the accusations of the report: that such techniques were ineffective, unsanctioned by the chain of command, constituted torture, and frequently used with seeming arbitrariness. He was especially insistent to refute the idea that techniques such as waterboarding were equivalent to torture. The CIA, he suggested, over and over again, “very carefully avoided” doing anything legally recognisable as torture.

But when being questioned as to whether imprisoning and interrogating the innocent was really a price worth paying for so-called actionable intelligence (a point disputed in the report itself), Cheney became heated. “I have no problem as long as we achieve our objective…to get the guys who did 9/11 and…to avoid another attack against the United States. I was prepared and we did…It worked. It [has] worked now for 13 years.”

In Cheney we see an exemplary instance of what Freud calls ‘kettle logic’, where the dream-work allows two contradictory positions to coexist at once (‘I didn’t borrow your kettle in the first place’; ‘It was fine when I gave it back to you’; ‘It was broken when you loaned it me!’) Cheney suggests something similar, as though to say, we didn’t torture anyone, the report is a load of rubbish; we had to torture all those people, they were terrorists, they wanted to kill us—and you should be glad we did what was necessary! I felt Cheney had thrown down something of a challenge. A gesture so blatantly amenable to Freudian interpretation surely called for a response. What comment might psychoanalysis have on the institutionally approved, though simultaneously disavowed, exercise of state-sanctioned torture?

Frantz Fanon provides a first port of call, for there are surprising links to be made between this revolutionary psychiatrist and US foreign policy of the last two decades. I am not the first to make the connection. Indeed when, in the ’90s, hawkish US-neocon journalist Thomas Friedman extolled the virtues of liberal capitalism and suggested the salve it could provide to regions of the world that were fostering dangerous fundamentalisms, he alluded to Fanon on the way: “the wretched of the earth want to go to Disneyland not to the barricades”. Likewise, six months into the Iraq war in 2003—itself perhaps a misguided attempt to put Friedman’s principle into practice—the Pentagon screened Gillo Pontecorvo’s The Battle of Algiers (1966), a film that gave special cinematic force to the kind of political struggle that Fanon had embraced. The hope, presumably, was that the film might be of relevance, in shaping the US’s own counterinsurgency strategy.

Such fleeting references to Fanon, and the Battle of Algiers invite our curiosity. The Wretched of the Earth, Fanon’s 1961 treatise on the vicissitudes of decolonizing nation and mind, has as its penultimate chapter ‘Colonial War and Mental Disorders’. Case by case, it examines the effects of torture and violence—on both sides—on combatants and civilians who lived through the Algerian War. Its position at the end of the book confirms the point that whilst the struggle for national liberation is keenly felt to be contested, won, lost, and impeded on the streets, the struggle of the coloniser and the colonised ultimately is to continue on the terrain of the psyche itself, long after weapons have been put down, or the tortured provided “rest and peace”, as Fanon puts it. In this way this section of the book attempts to hold together the historical specificity of Fanon’s revolutionary theory and the existentialist psychiatry of his more poetic and abstract Black Skin, White Masks (1952).

In discussing the Senate Report at the Forum on Psychoanalytic Thought, History and Political Life¹, we wondered what Fanon’s case studies might tell us about the relationship of trauma and history, which had been the topic of our previous discussions on the psychoanalyst Sandor Ferenczi’s famous paper ‘The Confusion of Tongues’ and the theorist Ruth Leys’ response to it. How might Fanon’s insights into the after effects of the Algerian War shape the way we think about ‘where’ or ‘when’ trauma is located, and the relationship of ‘internal’ and ‘external’ psychic forces? Ferenczi was concerned with the way interpersonal behavior, not least adult sexual abuse of children, could have traumatic effects, leaving lasting forms of psychic devastation and fragmentation that psychoanalysis must set out to repair. Freud had no doubt that traumatic events ‘really do happen’, but he regarded them as supplementary to forces already at play within the psychic life of the subject and the power of the drives. Needless to say, both positions I have sketched here (albeit at the risk of caricaturing both Freud and Ferenczi’s stances) have significant moral and political implications for how analysts, and the wider society, respond to trauma as such.

Perhaps surprisingly the word ‘theory’ is only used once in the 525 pages of the Senate Intelligence Committee report. But nonetheless the work of two key CIA contractor-psychologists, James Mitchell and Bruce Jessen (codenamed ‘SWIGERT’ and ‘DUNBAR’ respectively), was grounded on specific ideas about human motivation and development. Interrogation methods were intended to induce ‘learned helplessness’ “in which individuals might become passive and depressed in response to adverse or uncontrollable events.” Indeed, we read in the report that Mitchell and Jessen had honed their craft at the US Air Force SERE (Survival, Evasion, Resistance and Escape) school, where they had written papers and conducted research on topics such as ‘resistance training’ and ‘captivity familiarization’. Many of these techniques are now notorious, such as ‘walling’, the ‘attention grasp’, and forcing prisoners to wear diapers. Waterboarding in particular is described as “a tool of regression and control”.

The rationale of this ‘learned helplessness’—in which, for instance, a detainee may be offered a bucket to defecate in as a ‘reward’—is clear: prisoners are subject to arbitrary and contingent shocks to wear them down to the point of cooperating. Fanon notes that one of the symptoms of patients constantly subjected to use of the ‘truth serum’ (pentothal) is “fear amounting to phobia of all private conversations.” “This fear”, he writes, “is derived from the acute impression that at any moment a fresh interrogation may take place.”

Likewise in a passage on the effects of ‘brainwashing’ techniques, in which Fanon alludes to French authorities’ using methods honed by Chinese communists to ‘re-educate’ their enemies, Fanon notes in the case of one brainwashed intellectual that prisoners would be told they would be freed—and meeting would be arranged a few days before this date to give them the opportunity to show the progress they had made in denouncing the revolution. However, at the end of the meeting, ‘the decision is often taken to postpone setting the prisoner free, since he does not seem to present all signs of a definitive cure.’

Such capricious and unexpected changes were intended to disorient prisoners and leave them utterly dependent, as in a regression, on their captors. The symptom this results in, Fanon notes, is “the impossibility of explaining or defending any given position…everything that is affirmed can, at the same instant, be denied with the same force.” Fanon notes that brainwashing ‘for non-intellectuals’ works by demolishing and breaking the body rather than taking subjectivity as its starting point. This is still suggestive in understanding the CIA’s techniques, detailed in the Senate Report, involving both physical and non-physical attempts to achieve a state of complete compliance, through the prisoners’ experiences of random, uncontrollable, and unforeseeable processes, that induce a state of ‘learned helplessness’.

These techniques, however, are not new. Whatever the still earlier precedents, in the custodial practices of previous states, they owe a good deal to familiar Cold War experiments and practices, for instance the methods used by the North Vietnamese on US airman in the 1960s, by communist China during the Korean war, and within the CIA’s own coercive interrogation programme, the KUBARK Counterintelligence Interrogation Manual. They were “never intended to be used against detainees in U.S. custody”, one footnote tells us. The manual itself draws on concepts and language not unfamiliar to historians of psychoanalysis and psychiatry, identifying as “principle coercive techniques” “heightened suggestibility and hypnosis, narcosis and induced regression.”

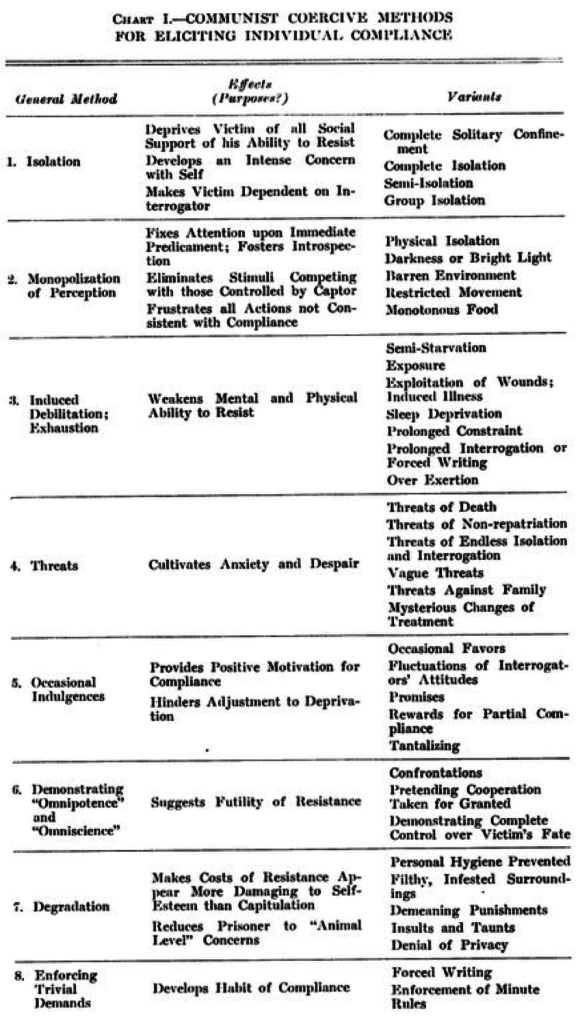

A chart describing techniques used by Chinese Communists to ‘re-educate’ their enemies, which later informed the CIA’s enhanced interrogation program, as presented in Albert D. Biderman, “Communist Attempts to Elicit False Confessions from Air Force Prisoners of War” Bulletin of New York Academy of Medicine Vol 33, No. 9 (Sept 1957)

I was reminded here of Fanon’s discussions of the use of ‘truth serum’ in interrogations by the French, and the way in which the process of brainwashing used on ‘intellectuals’ requires them to “take various roles in a veritable game of activity.” In this process, “Anyone can play any role; it even happens that in a single day a person’s role may be changed; symbolically you may put yourself in the place of anyone you please.” The brainwashed intellectual was required to “play” the game of collaborator and informer, and “lead a double life.” For instance, he would be told simultaneously that his views on revolution were unacceptable and “that he is a man well known for his patriotism and that he is imprisoned for preventative reasons.” The indeterminacy of the prisoner’s status—is he hero or traitor—is key to the process.

The violence of the ideological conflicts and proxy wars of the last fifty years are re-routed into such contemporary strategies. It is as though ‘enhanced interrrogation’, as practised by the CIA, constitutes something akin to a return of the repressed. At the end of Meet the Press, Chuck Todd asked Cheney about waterboarding again:

CHUCK TODD:

When you say waterboarding is not torture, then why did we prosecute Japanese soldiers in World War II for waterboarding?

DICK CHENEY:

For a lot of stuff. Not for waterboarding. They did an awful lot of other stuff to draw some kind of moral equivalent between waterboarding judged by our Justice Department not to be torture and what the Japanese did with the Bataan Death March and the slaughter of thousands of Americans, with the rape of Nanking and all of the other crimes they committed, that’s an outrage.

Whilst it would be crude to draw any direct equivalence between the Japanese torture of POWs in World War II and the CIA’s morally compromised interrogation procedures, it is striking that Cheney’s defensiveness and his attempts to justify what the CIA had done with prisoners rest on his assumption of a kind of moral absolutism—us and them—that the use of torture itself undermines. (Torture, he says, is “what 19 guys armed with airline tickets and box cutters did to 3,000 Americans on 9/11”).

But as Fanon shows us in his reflections on brainwashing, the very interchangeability of ‘roles’ or subject positions, and the moral ambiguity for everyone involved in the process, is central to how torture ‘works’. Is the intellectual patriot or traitor, imprisoned for ‘their own safety’, or because they are a subversive? We might ask similar of the torturer. As Fanon also points out, torturers too may just as often appear in the guise of a doctor as they might in a policeman’s uniform. This, Fanon says, is “the medical form that ‘subversive war’ takes.” For Fanon, writing and philosophy hoped “to make explicit, to demystify, and to harry” precisely that violence—and the double standard on which it rests—Cheney would disown: what he calls, in The Wretched of the Earth, “the insult to mankind that exists in oneself.” His project is ongoing.

¹Benjamin Poore teaches literature at Queen Mary, University of London. He is also currently researcher-in-residence at the Freud Museum London, a post funded by the AHRC. These reflections stem from discussions at the forum, ‘Psychoanalytic Thought, History and Political Life’, a series convened since 2004 by Prof. Jacqueline Rose and Prof. Daniel Pick and now organised by a group of doctoral students and post-doctoral researchers, under the auspices of the Institute of English Studies, Senate House, London University.