A still from the film Obedience (1962), a production by the psychologist Stanley Milgram made in the course of his ‘Obedience to Authority’ experiments at Yale University. It is now widely believed that these experiments could not be recreated today due to ethical guidelines established by psychologists in 1973.

By Laura Stark

‘I do feel that the problem of maintaining highest ethical standards of behavior among psychologists is an ongoing problem, a necessary, continuing process.'[1]

In 1958, an esteemed child psychologist dispatched this sentence from the university campus from where I now write in Nashville, Tennessee. But the sentence might well have been composed in 2015. On the heels of a damning report from an independent review committee, the American Psychological Association (APA) is now weighing how it might change the profession’s ethics policies—and whether to revamp the very process through which the association changes its rules in the first place, a meta-policy of sorts.

Prof. Nicholas Hobbs. Image courtesy of George Peabody College Photographic Archives, Vanderbilt University Special Collections.

In 1958, Nicholas Hobbs had sent pages of feedback from Nashville to the chairman of the APA committee that had recently written the association’s first modern ethics code. Seven years later, Hobbs was elected president of the APA and tasked with appointing yet another committee. This one would overhaul the organization’s fresh code of ethics since, as he thought, the ethics codes should be revised every five years. In appointing the six men who would form the new committee, Hobbs also determined their approach: the committee would survey psychologists across the country for ‘critical incidents’, that is, personal accounts of moments in psychological practice when questions of professional ethics seemed in particularly sharp focus. Hobbs thought it the best way to acknowledge the new problems faced by everyday psychologists, who would be asked to report ethics violations, both mundane and extravagant, to the APA.

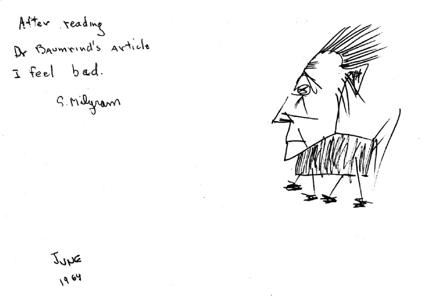

Stanley Milgram’s self-portrait from June 1964. Milgram wrote on the sketch: “After reading Dr Baumrind’s article I feel bad.” Milgram was referring to Diana Baumrind’s published criticism of his use of deception in the Obedience to Authority studies. Yale University, Stanley Milgram Papers, c17, f246.

In the 2015, most people, myself included, have paid closest attention to the work of only one APA ethics task force that was chronicled in the final report of the independent investigation issued in July. Revelations about the association’s Presidential Ethics and National Security task force have been the lightning rod for APA criticism, and rightly so. APA leaders made changes secretly and specifically to protect military psychologists so they could continue working for the Department of Defense—aiding torture and interrogation—without having a professional ethics conflict.

Yet the independent investigation also considered a second ethics task force. The work of this task force has been all but forgotten but is equally interesting. The final report chronicles the work of the APA’s ethics committee that revised the association’s main ethics code soon after the 9/11 attacks. The investigation’s aim was to learn whether changes to the main APA ethics policy also came from leaders’ hidden motive to stay in the good stead of the US government. There has been little attention to this task force because investigators found that this committee did nothing wrong.

Why? Was it a triumph of individual integrity, or the vindication of the ethics-making method? No. The buffer against corruption was, in a word, laziness. The final report explains that the committee never got around to making the changes they considered and that might have pressed the boundaries of appropriate ethics-making procedure.

What is amazing is that this twenty-first century ethics committee had continued to use the same process as Hobbs had outlined as APA president in 1965:

‘I think we need to start from scratch, collecting critical incidents as we did before in order that we can get a good sense of what the problems really are and not be guided solely by our assumptions.'[2]

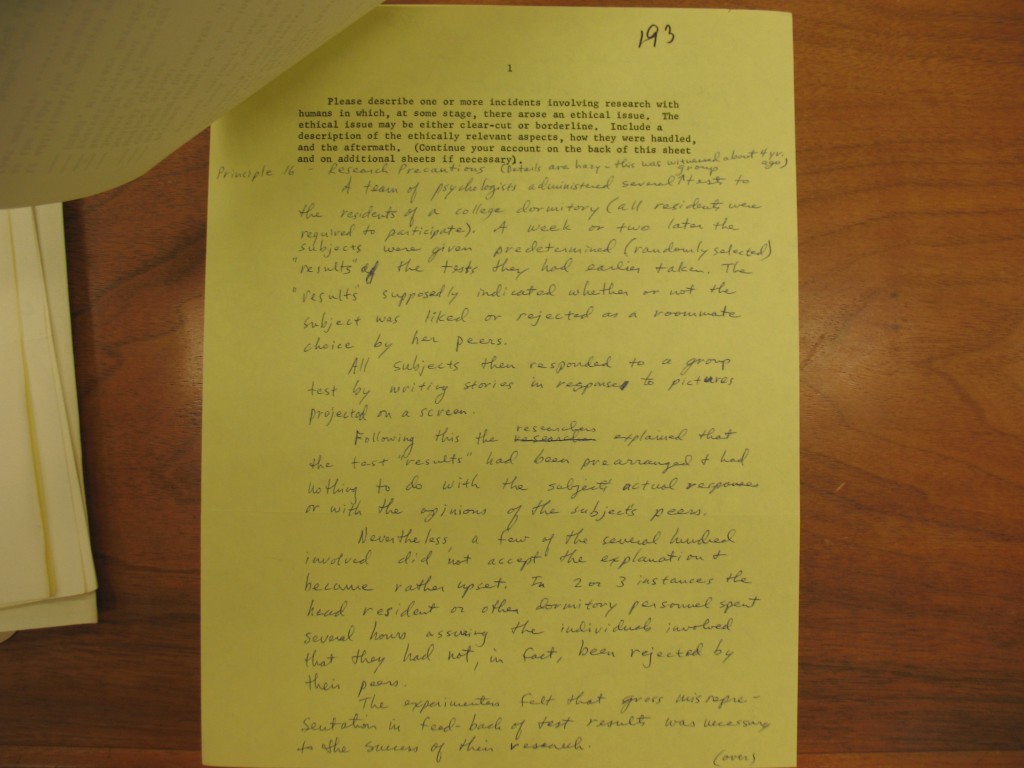

Starting in 1965, Hobbs recruited a team of six top American psychologists who collected incidents and wrote the APA’s landmark and lengthy 1973 ethics principles over the course of seven years. Thousands of original ‘critical incidents’ reported by 1960s psychologists, as well as other documents related to the committee’s work, are archived at the US Library of Congress. I’ve written about the committee’s process of interpreting the 1960s critical incidents—which are shocking, hilarious, and invaluable for historians.

By 1969, they had mailed the questionnaire to 9000 psychologists and already gotten 1000 responses, which the committee started reading [3]:

‘A faculty member administered drugs (hallucinogens) to student volunteers as part of what he described as a research project. The faculty member was not competent in psychopharmacology and was unfamiliar with the literature dealing with side-effects, physiological complications, etc. He had taken no steps to inform his subjects that such possibility existed. In subsequent discussion he defended this position by arguing that as it was not certain that dangerous consequences might ensue he was under no ethical obligation to warn his subjects that the possibility of untoward effects existed, as such a warning would frighten them away from the research and it was not absolutely clear that any real danger might develop…'[4]

From drugs and alcohol, to consent, privacy, and military work, the psychologists’ concerns ran the gamut.

By collecting and interpreting thousands of critical incidents, the APA aimed to follow a procedure that was purportedly inductive and free of bias. The process was intended as a democratic, scientific, exhaustive technique for creating rules all psychologists could support, if not in content, then at least in principle. The association has stuck with the method ever since.

Fifty years later, the association uses the same unusual technique for writing ethics codes. As the 2015 final report describes, the APA still surveys vast numbers of psychologists about their views and opinions, then lets a small set of luminaries write the rules. In other words, the APA created and has continued to use an elaborate, expensive, and labor-intensive method for creating professional ethics that seemed beyond human intervention.

Yet the everyday work of making an ethics code is just like the everyday work of making scientific facts. As historians of science and medicine know, scientific facts are shaped by the ways in which real people, in real physical places and social circumstances, make them up—to use Ian Hacking’s apt phrase. The same is true for ethics.

Like the scientific method, what is remarkable about the APA’s method of making ethics is not its failure, but the endurance of practitioners’ faith in a method so illusory.

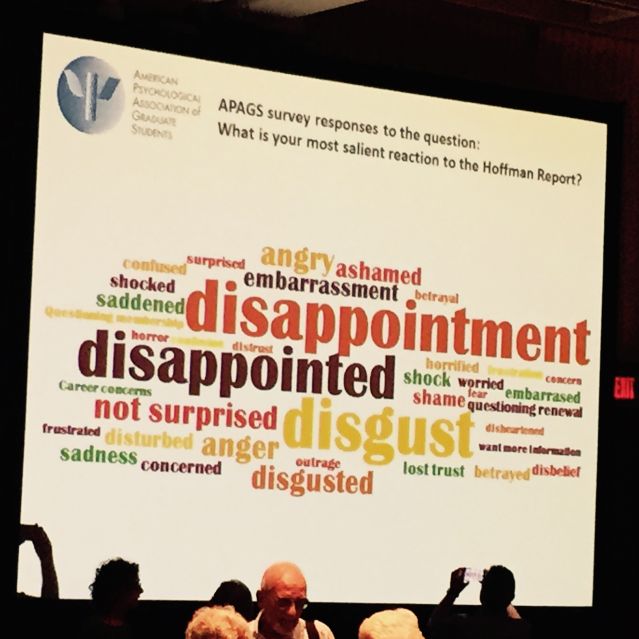

An image from the APA Annual Meeting, held August 2015 in Toronto, where psychologists discussed their reactions to the independent report detailing the APA’s complicity in the US government’s policy on enhanced interrogation.

Notes:

[1] Letter to Wayne Holtzman from Hobbes on July 31, 1958, Folder 2: Committee on Scientific and Professional Ethics and Conduct, 1954-60, Container 414, archives of the American Psychological Association, US Library of Congress, Washington, DC.

[2] Hobbs to Stuart Cook, Dec 20 1965. Folder 5: Ethical Standards in Psychological Research, Correspondence Internal B-H, 1965-1971, Container 426, APA.

[3] Minutes March 7-8 1969 of Board of Scientific Affairs (BSA), Folder 10: Ethical Standards in Psychological Research: Agenda, minutes, items, 1968-72, Container 415, APA

[4] Q 2069, Folder 3: Ethical Standards in Psychological Research. Questionnaires. Sample I. Miscellaneous Problems, General. Container 433, APA.

Dr. Laura Stark is Assistant Professor of History and Assistant Professor at the Center for Medicine, Health and Society at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tennessee. She is the author of Behind Closed Doors: IRBs and the Making of Ethical Research (University of Chicago Press, 2012), and several other works on the history of medicine, morality, and the modern state, as well as pieces on social theory. Her current research explores the lives of ‘normal control’ research subjects enrolled in the first clinical trials at the US National Institutes of Health after World War II. http://www.laura-stark.com/

This post was edited for the web by Marcia Holmes.

Related post: What We’re Reading Now: The APA Report