This post has been contributed by Dr Andrew Atter, founder and CEO of Pivomo and Visiting Fellow, CIMR; and Usman Salim, Founder and CEO of Liontech Studios

This post provides some background on our forthcoming webinar examining to what extent gaming technology can provide a catalyst for adult learning, especially in that hard to reach demographic group termed the “NRS cohort” (DofE 2020) i.e. young adults (GenZ) in insecure employment and often hard-to-reach through formal training and education institutions (NESTA 2020).

Women are over-represented in this cohort (APPG 2020). An employability deficit created in the school system is amplified, not reduced, by the job market (APPG 2020). Caught in a loop of failure and alienation, school leavers are too often lost to institutionalised learning altogether, creating long term implications for adult learning and their adaptation to AI-driven automation.

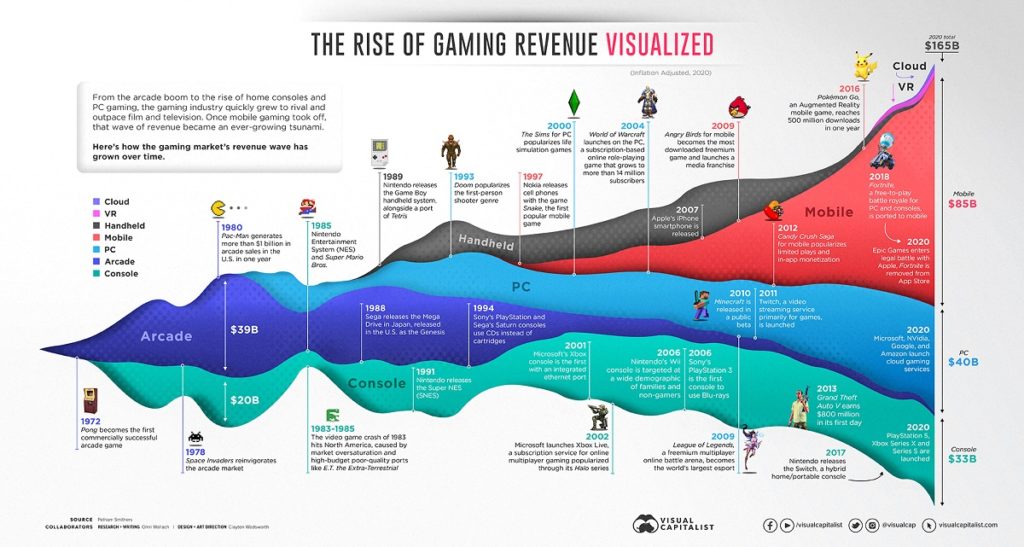

Ironically, the NRS cohort are major users of gaming, a crucible of AI and cloud-based technologies (UKIE 2019). Women make up 48% of the 32 million UK gamers (and 46% of 2 billion worldwide), and while still underrepresented, are a growing force in the game design industry (CIC 2019).

We know that there is a high non-completion rate from MOOCs and even in conventional adult training, 90% of the potential learning is lost over a year (Silverman 2012). Can gaming provide an alternative approach?

In this webinar, we will ask whether we can we find a way of integrating game design and learning design in order to tackle underlying patterns of social inclusion, de-skilling and risks from automation (Leslie 2019)?

Our public discourse on gaming is shaped by concern for school children, and this is amplified in our media. Generally speaking, public concern has been rising in recent years. For instance, in 2019, as part of the Digital Harms programme, the UK Digital Minster calls for introduction of the PEGI game ratings; and in 2020, the DCMS Report urged regulation of “immersive gaming technologies” (DCMS 2020).

The research to underpin these positions presents a mixed picture:

- A 2019 report in the Daily Mail highlighted Spanish research in bold headlines:

“Children who spend hours watching television and playing video games do worse at school, study claims” (Chalmers 2019) .

- In a 2020 study by researchers from the University of Linz concluded the following:

“…playing computer and video games can result in a noticeably, albeit small, loss of educational returns, but it does not affect basic competences” (Gnambs, Stasielowicz et al. 2020).

- On the other hand, the Guardian reported on a study Australian study involving 12,000 children, which found that those kids “who play online video games tend to do better in academic science, maths and reading tests” (Gibbs 2016).

- A 2017 study by the University of Oxford’s Internet Institute identified the positive benefits between gaming and mental well being, and contradict the DCMS findings and criticise much of the research to date. They write:

“Overall, the evidence indicated that moderate use of digital technology is not intrinsically harmful and may be advantageous in a connected world.” (Przybylski and Weinstein 2017).

The association of gaming with violence, which are overwhelmingly the preserve of (some) male gamers, has possibly blinded policy makers to the possibilities that lie in the wide variety of other game types, such as role playing, discovery, problem solving, e-sports and creative gaming, that form the bulk of the gaming industry, and are the preference of most female gamers (Brown 2017).

Dr Jane McGonigal, who wrote in 2011:

“…in today’s society, computer and video games are fulfilling genuine human needs that the real world is currently unable to satisfy. Games are providing rewards that reality is not. They are teaching and inspiring and engaging us in ways that reality is not. They are bringing us together in ways that reality is not” (McGonigal 2011).

The gaming industry appears to be succeeding in exactly the areas traditional education and adult learning is struggling, by designing in

- Identification and immersion

- Engagement and motivation

- Self efficacy, mood shift and social connection (Kowert 2020)

- Higher cognitive abilities, such as diagnosis, strategising, decision-making

- Bite-sized in game learning, progression, rehearsal and review

- Calibration of failure/reward, and need for tenacity, tolerance of failure and repetition

(Plass, Homer et al. 2014)

One reason this field is so hard to research is the sheer pace at which the industry has evolved. High quality games can now be delivered to basic mobile devices, in low bandwidth environments. This is in stark contrast to the digitally bulky content needed for conventional online learning and zooming.

The original NRS report highlighted the learning needs of this cohort, as follows:

· “the ability to use a device that is convenient to the individual, for example, a mobile phone”

· “the choice of different learning media to suit different situations and preferences”

· “accessible platform features with content design that works on mobile phones” (DofE 2020).

The public debate about how to marry together the twin towers of gaming design with learning design has started. There are intriguing green shoots. Recent research compared 4 different methods, including video gaming and the conventional lecture format. The results suggest that video games can at least match the learning outcomes of the traditional lecture.

“The results of this study indicated that, with one exception, there were no significant differences in outcomes between the four different methods of instruction. The broad interpretations of this study are that educational outcomes of using educational video games may not vary greatly based on social context when using precise definitions of competition and cooperation. Importantly, this affords educators the general freedom to choose among a number of social educational structures without fear of significantly compromising educational outcomes”. (Erickson and Sammons-Lohse 2020)

The key question remains: What happens if we allow learning-based games to run “in the wild”?

We hope the CIMR webinar will help fuel the public debate, highlight some options and point towards further research.

Bibliography

CIC (2019). “UK MARKET OPPORTUNITY.” from https://www.thecreativeindustries.co.uk/industries/games/games-facts-and-figures/uk-market-opportunity#:~:text=Gamer%20population%3A%20Approximately%2032.4m,per%20cent%20of%20all%20players.

DofE (2020). National Retraining Scheme: Key Findings Paper. Education, UK Government.

Loo, S. and B. Sutton (2020). Informal Learning, Practitioner Inquiry and Occupational Education, Routledge.

NESTA (2020). “CareerTech Challenge Fund: Meet the innovators.” from https://www.nesta.org.uk/project-updates/careertech-challenge-fund-meet-grantees/.

UKIE (2019). “UK consumer spend on games grows 10% to a record £5.7bn in 2018.” from https://main.ukie-website-prod.etchplay.com/news/uk-consumer-spend-on-games-grows-10-to-a-record-5-7bn-in-2018.