Whether precarious conditions are extended indefinitely, or whether, within the pendulum swing of a wrecking ball, the apparently solid is made ephemeral, the line between the temporary and the permanent can be a fine one. The second in a series of workshops at the ICA – ‘on the social in architecture’ (supported by CHASE and co-organised by Birkbeck’s Architecture Space and Society Centre) – brought this ambiguity to the fore. The workshop on 9th March 2018 focused on questions of architectural heritage, memory, displacement and control in postcolonial and neocolonial contexts. Alistair Cartwright wrote a blogpost after the workshop.

Romola Sanyal from LSE’s department of Geography and Environment opened the discussion with an examination of Lebanon’s current ‘no camp’ approach to refugees. This relatively recent policy represents, in principle, a shift away from the rigid environment of the camp. Sanyal talked about how the latter traces its origins back to British concentration camps in the Boer war (and before that, perhaps, to military encampments). Since then, refugee camps have become standardised; blueprints contained in the UNHCR’s ‘WASH’ code (Water, Sanitation and Hygiene) offer one of the most up-to-date formulae. Yet despite being conceived as emergency shelter for displaced persons, camps in Lebanon – the country has the highest number of refugees per capita – have existed for many decades, going back to the Palestinian Nakba of 1948. Shouldn’t we think of these ‘camps’ as cities, which is exactly what many of them look and feel like?

The ‘no camp’ policy aims to short-circuit the future possibility of such permanent camps emerging from the massive displacement of people across Lebanon’s border with Syria. The aim is to house new refugees in either private rented accommodation in cities, or in more dispersed rural settlements. However, as Sanyal showed, the policy has led to problems of its own, with developers in Lebanon’s overheated housing market accelerating speculation and subdivision. Standards for upgrading buildings designed to combat this tendency have put some NGOs in the unusual position of acting as enforcers of building regulations. Will we see a new field of contestation emerge at this crossroads?

The ‘no camp’ policy aims to short-circuit the future possibility of such permanent camps emerging from the massive displacement of people across Lebanon’s border with Syria. The aim is to house new refugees in either private rented accommodation in cities, or in more dispersed rural settlements. However, as Sanyal showed, the policy has led to problems of its own, with developers in Lebanon’s overheated housing market accelerating speculation and subdivision. Standards for upgrading buildings designed to combat this tendency have put some NGOs in the unusual position of acting as enforcers of building regulations. Will we see a new field of contestation emerge at this crossroads?

As it stands, the sometimes higher standards of structures rebuilt under the guidance of humanitarian initiatives has meant ‘normal’ informal settlements often escape attention. Perhaps it’s time, as Sanyal argues, to move away from the discourse of ‘the camp’, and to think more about a generalised informal urbanism.

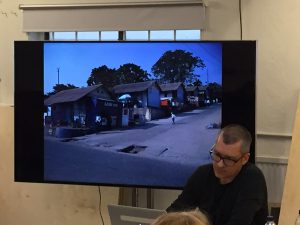

Our second speaker of the day was Rachel Lee, from TU Berlin’s Habitat unit. In Dar es Salaam, Tanzania – where Lee has worked for a number of years on questions of postcolonial heritage – so called ‘stealth demolitions’ are not uncommon. Here we witness the opposite movement to the one seen in Lebanon’s refugee camps: the apparently permanent vanishing, quite literally, overnight. Often these demolitions are carried out by private developers and businessmen, and take place on government owned land in poor neighbourhoods. The displacement they cause can go hand in hand with a very real loss of history.

As Dar es Salaam has experienced explosive growth since the 1970s, vibrant quarters of the city like Kariakoo market and what’s known as the ‘Light Corner’ have come under threat. (A new shopping centre is putting itself forwards as a replacement for the former, while casualties of the latter’s redevelopment include the offices of Antony Almeida’s world renowned architectural practice). All of which raises questions about what we count as architecturally, or historically, valuable.

As Dar es Salaam has experienced explosive growth since the 1970s, vibrant quarters of the city like Kariakoo market and what’s known as the ‘Light Corner’ have come under threat. (A new shopping centre is putting itself forwards as a replacement for the former, while casualties of the latter’s redevelopment include the offices of Antony Almeida’s world renowned architectural practice). All of which raises questions about what we count as architecturally, or historically, valuable.

These questions are not necessarily unique to postcolonial contexts, as Lee points out. Modernist architecture can fall on either side of the revered or detested, whether we label it ‘tropical’ or ‘nordic’. And urban heritage that goes beyond existing ‘formalistic and bureaucratic’ qualifications can be just as hard to define in London, as in Dar es Salaam. A technique Lee has found valuable in capturing the elusive heritage of lived experience combines oral history interviews and walking practices. How might testimonies including stories and regularly trodden paths be not just recorded but recognised, and given value? And what consequences might that have for the built environment?

This could, at one level, be a question of scale, as Johan Lagae (professor in Architectural History at the University of Ghent) demonstrated in the day’s final session. The middle ground, Lagae suggested, is precisely the view that reveals nothing new about a city. In order to gain new knowledge about urban experience we need to either ascend to the macroscopic scale (the aerial view, for example), or descend to the level close-up image, the personal testimony and the everyday.

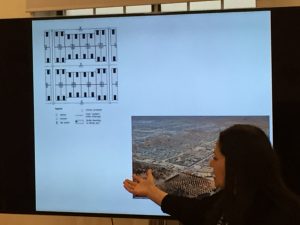

Seeking out these revealing scales proved crucial in Lagae’s recent work mapping urban heritage in Matadi, in westerd DRC on the banks of the Congo. This was, as Lagae stated from the beginning, a ‘messy’ project – a major national and international piece of heritage research with funding from the World Bank. (A fact which still leaves me asking when non-participation, or a straight up ‘no’, would be the best answer). If Architecture moulds, directs and exerts power, then architectural history can play a powerful legitimizing, or delegitimizing, role. This is a role which Lagae himself sets out to question.

Seeking out these revealing scales proved crucial in Lagae’s recent work mapping urban heritage in Matadi, in westerd DRC on the banks of the Congo. This was, as Lagae stated from the beginning, a ‘messy’ project – a major national and international piece of heritage research with funding from the World Bank. (A fact which still leaves me asking when non-participation, or a straight up ‘no’, would be the best answer). If Architecture moulds, directs and exerts power, then architectural history can play a powerful legitimizing, or delegitimizing, role. This is a role which Lagae himself sets out to question.

While the project’s funders wanted to limit the documentation to urban infrastructure, focusing on roads and waterways, even within this limited framework sites of contestation opened themselves up, if one cared to look deeper. A particular bridge over a tributary running through the city (labelled at times an ‘open sewer’) proved an unlikely heritage candidate due to its important place in Matadi’s labour history: striking dockers staged a blockade on the bridge in 1945.

This mundane structure was loaded with a history of struggle. Labour more generally – and Belgium’s history of colonial violence – are an ineradicable part of the city fabric. Even some aspects of the street pattern can be traced back to the layout of colonial labour camps. As Lagae argued, it is in the friction between the land and the grid imposed on it, that the layers of ‘patrimoine’ are to be found.

Leave a Reply